- Home

- Lynne Alexander

The Sister Page 7

The Sister Read online

Page 7

‘‘Where are the others?’’ he managed, righting himself.

‘‘Rob has gone back to Wisconsin. Wilky is too ill. William, as you know … .’’ Henry mopped his brow, his poor head all a-sweat. He was exhausted. I pictured him trapped on that sluggish ship for days and days pacing the deck, urging it forward. Finally, he consults the Captain, who explains they are having engine trouble. ‘‘Is there nothing to be done? I am due at a …’’ Here he hesitates: would ‘a professional engagement’ carry more weight than ‘my father’s funeral’? He decides upon the former. The Captain shakes his head, he is very sorry but there is nothing for it. Henry stands gripping the railing, staring into the sea. ‘‘I am going to miss my father’s funeral,’’ he confesses. The waves cannot care less: laplap, they sing.

Henry took to his attic bed, I to mine. Aunt Kate looked after us both, bringing us cups of tea and bowls of weak broth. Up and down she went. In between, she began sorting through some letters which she’d found in father’s chest of drawers. I slept on, dreaming of papers being burnt.

When we were well enough Henry and I returned together to the Cemetery. I watched from a distance, ankle-deep in snow as he stood at our father’s newly-cut grave with William’s letter flapping at his thigh. It was late in the day; above him the western sky had turned into a deadly polar pink behind the bare branches of the winter woods. Henry removed his hat tucking it under his arm to protect it from the wind, and as he did so the moon came up, white and young, and was reflected in the white face of the empty Stadium which framed one of the boundaries of Soldiers’ Field across the Charles. He stood on the little hillock by the group of graves that made up our family. As he read, I saw that he was moved by everything he had once known, and with it came a recognition of the stillness, the strangeness, the American-ness. And the words. Written words are like injections, I thought, they pass directly into the bloodstream. Our bodies get in the way, whereas words are life. He began: Darling old father …

How odd, I thought, for Henry to be reading William’s words. But he was used, after all, to erasing himself, to becoming phantom-like. His was a gift for not getting in the way. Indeed, he soon became so transparent I could see William standing there hunched over his own letter. William, ever the responsible one, promises to look after the literary remains. He also promises that the brothers will stand by one another, and also stand by their sister Alice. He is full of tender memories and feelings in his heart but ‘‘you, Father’’ he finishes in Henry’s voice, ‘‘will always be for me the central figure. Good night, my sacred old father. Your William.’’

Now Henry must fish for his handkerchief: an awkward manoeuvre what with having to keep hold of his hat and the letter. Eventually he manages to wipe his nose. When he is sufficiently composed he places his hat back upon his head, gives it a one-fingered tap, pockets William’s letter and backs away. It is a signal that I am to come forward, which I do, only my lips are rolled in upon themselves. If I open my mouth a howl will emerge. I shake my head. I have nothing to offer. I am frozen in time and space. I cannot feel my feet. Henry places a hand at my back and leads me away as if I were a very old person.

Ten

The recently opened and conveniently located Adams Nervine Asylum had been endowed specifically for the treatment of ‘nervous people who are not insane.’

‘‘I trust I am not insane,’’ I told the interviewing panel, ‘‘merely dilapidated.’’ Dr. Mitchell looked away; the others harumphed.

My mother and father were dead; my dear friend Katharine was swanning about the country ‘selling’ her Home Studies Course to other female educationists; Henry was in London working on a novel set in Boston; William was teaching at Harvard; Wilky was down in Florida recuperating and Rob was ‘drying out’. And, yes, I’d done precisely what I’d once blamed him for doing: asylum, a place of refuge or sanctuary.

I admitted myself in the spring of 1883.

I was given a tour of the house and grounds. ‘‘Adams House is built in the Queen Anne style of architecture,’’ the manageress helpfully informed me. ‘‘I guess Queen Anne had a sense of humor,’’ I rejoined. Frankly, I thought it a disproportionate abortion with its excrescenses of cupola and turret, its girdling porch (‘‘an especially American feature’’), its claustrophobic restraining posts and struts. Had one of its inmates, I inquired, designed it in one of her more lurid nightmares? No reply. It had chillingly weedless lawns and ‘‘sixteen acres of mature woodland.’’ I saw that it would do as a setting for one of Henry’s gothic tales. Or mine, should I ever write again.

‘‘You are quite relaxed, Miss James?’’ Dr. Mitchell inquired. I was all too relaxed having survived a steam and massage treatment. ‘‘I feel like a fat pink shrimp,’’ I reported, tongue protruding. ‘‘Good good,’’ he responded, up-ending his pen upon its vulnerable nib. Now, if I was ready, he would present me with a list of words. ‘‘It is a newly concocted method for tapping into an unusual or, shall we say, pre-conscious state of mind.’’ ‘‘Yes, I know,’’ I said, ‘‘my brother has spoken of it: based on an association of ideas.’’ ‘‘Your brother?’’ He blinked. ‘‘William.’’ ‘‘William James?’’ ‘‘The same.’’ ‘‘I see. Well.’’ He shifted about in his leather chair in an attempt to reassert his authority. ‘‘If you are ready we can begin. Simply say the first word,’’ he instructed, ‘‘that comes into your head.’’ I announced I was ready, and he began:

‘‘Egg?’’ ‘‘William.’’

‘‘Feather?’’ ‘‘God.’’

‘‘Wedding?’’ ‘‘Death.’’

‘‘Did you say ‘dress’, Alice?’’

‘‘No, Dr. Mitchell, I said ‘death’.’’

‘‘Ah.’’ He continued:

‘‘Death?’’ ‘‘Father.’’

‘‘Father?’’ ‘‘Silly.’’

He cleared his throat:

‘‘Pen?’’ ‘‘Henry.’’

‘‘Marriage?’’ ‘‘Mistake.’’

‘‘Marriage?’’ he repeated. ‘‘Aunt Kate.’’

He sat back in his chair. ‘‘Fine, excellent.’’ He’d flipped the pen over so that it now stood on its holder end: taptap.

‘‘Tell me about your Aunt Kate,’’ he said.

‘‘She lived with us.’’

‘‘And why was that?’’

‘‘She was useful about the house. She helped my mother to look after us.’’

‘‘But she was married …?’’

‘‘Yes, but it was not the usual thing …’’ Here I slid forward across his desk until I was close enough to make out a scar over his right eyebrow. ‘‘As a matter of fact,’’ I told him with relish, ‘‘it was scandalously brief.’’

Aunt Kate and I had been staying at Clifton House near Cambridge, just along from Marble Head. I was nineteen years old and needing to be ‘socially aired,’ having been isolated during my recurring illnesses. One day she led me out along the cliff path. At some point we stopped to gaze down at the churning waves hitting the rocks below. We stood close together; suddenly I turned to face her. ‘‘What about you?’’ I began. ‘‘What about me, Alice?’’ The other decrepit spinster-bitches and I had already compared notes. Marriage was their theme-song: Louise Wilkinson is now married, have you heard? … And Mary McKim has just landed a Mr Richard Church … And Serena Mason is promised to somebody else … and Ned Lowell’s engaged to a Miss Goodrich. Oh, and Kitty Temple’s friend Mary Hane has also done the deed and … marriagemarriagemarriage, until the world had begun to feel like a giant mating pen with only us, the sorry inmates of Clifton House, locked out.

Aunt Kate took my arm as my feet seemed to be going in different directions. ‘‘So am I to be trotted out like a bitch in heat?’’ I taunted her. ‘‘Concentrate on where you are going,’’ she admonished, obviously trying to distract me from ‘the subject’; but I would not be deflected from my purpose. What purpose, you well might ask, for it was obviou

s no good could come of it.

‘‘Your so-called marriage,’’ I pursued.

‘‘Never mind about that,’’ she waived dismissively. She’d warned us off the subject before, but I was determined not to be put off this time. ‘‘After all,’’ I insisted, ‘‘you know all about marriage: describe to me the joys of marriage.’’ I’d learned teasing from William: William who’d once made up an Ode To Aunt Kate, ending with:

O the gallant Captain perished for the love of Kate …

‘‘That’s cruel, Willie,’’ I’d objected: ‘‘how could you?’’ Our Aunt’s marriage had by then been annulled after only a year, though no one knew why. Something, we guessed, that her ‘husband’ Captain Marshall had done, or not done; but that he’d been anything but gallant was certain. Once, riffling through Aunt Kate’s jewelry box I’d come across a secret compartment containing a yellowed newspaper cutting from an ‘Obituaries’ page. My eye picked out the following: ‘Like many men, who have from early life been engaged in nautical pursuits, and accustomed to command … Captain Marshall had an air of sternness about him that was somewhat repulsive to strangers …’ After that I re-folded it and stowed it away, but the phrase somewhat repulsive to strangers stuck in my mind.

But there was Aunt Kate at my elbow with her innocent fat sausage curls and her never mind that. ‘‘Oh, I do mind,’’ I complained insisting: ‘‘and I will know.’’ For marriage, I think at this stage, must be like rain: it blurs things yet it is right because without it we die. (Would I die unwatered?) Being married, in spite of all the whispers about what happened to you afterwards – the disappointments, the failures, the unmentionables – had come to seem a necessary outcome. Perhaps it’s like flying, I thought, dangerous yet still somehow desirable. I pictured myself being pushed off a cliff and being caught and borne aloft by some gravity-immune hero called ‘a husband’. Music accompanies this ridiculous scene, Aunt Kate rippling through a Chopin waltz.

‘‘But you were married,’’ I cried, as if that were a better cure-all than Mrs Emerson’s homeopathy or William’s sea-baths or mesmerism or anything.

‘‘Oh,’’ said my Aunt, as if the very thought of it wearied her, ‘‘it all happened so long ago, Alice …’’. But then, as if she’d seen into the heart of a breaking wave: ‘‘And, as you know, it did not last long.’’

‘‘How long?’’ I demanded.

Her face hardened: ‘‘Just short of a year.’’ She prodded me on with one finger. ‘‘Best to let sleeping dogs lie, Alice.’’

‘‘Was he a dog? Did he turn vicious?’’ And then, recalling the obituary: ‘‘Was he as ‘repulsive’ to you as he was to strangers?’’

‘‘Alice! Enough! Suffice it to say it was a mistake.’’ After a pause, she shivered, then added in a barely audible whisper:

‘‘A frightful mistake.’’

The next day I was more determined than ever: I must, would, know more. Over breakfast I nagged and nagged until my Aunt got so fed up she blurted it all out. ‘‘Now see what you’ve done,’’ she cried, adding ominously: ‘‘You will regret it.’’

I stumbled off down the cliff towards the shore. The air was clear as anything, the October leaves turned to gold: perfect treasures, I thought giddily. The rocks awaited me below: some pointed, some smooth and banked like the backs of whales, fully as bold as the rocks at home, only without any surf. I kept up my descent until I reached a path then poured myself down gaining more and more speed until I couldn’t stop even if I’d wanted to because the rocks were loose and I was not used to running with my clumsy, weak legs, and with the speed and the slippage returned the secret I’d pulled out of my Aunt, the truth of her frightful mistake of a marriage. And she was right, I did regret it.

The good doctor’s mouth watered with curiosity as to the nature of the frightful mistake. ‘‘It’s the title of my tale,’’ was all I would reveal. He frowned, ‘‘Do you mean to say what you just told me was a fiction?’’ As if that was the same as ‘lie’. Well I would not reply to that. He threw down his pen. ‘‘I think that’s enough for today, Miss James, we don’t want to tire you out.’’ ‘‘I’m not in the least tired,’’ I objected. ‘‘And I enjoy telling stories – like my brother,’’ I added. At that he stretched forward again across his blotter, which was green and covered in inky doodles in the shape of bats with human heads: ‘‘That was not a game,’’ he said. It sounded like a threat. But if it was not a game, what was it? He was beginning to irritate me, to remind me of my father, and that made me want to knock his block off. But I controlled myself. I was by this time close enough to read the scribbles on his notepad: hysteria neurasthenia melancholia. The words were so used-up, so meaningless, he might have written dog cat pig with as much effect. I wanted to bang the desk with my fists, make the bats fly, then run round and pull his ears: But it is a game, don’t you see? A game of words containing clues to my distress which any nincompoop would guess! I almost felt sorry for him sitting there scratching his head. But then another part of me wanted to spit, You should not employ a new technique without knowing how to apply it, doctor!

On my way out, he stopped me: ‘‘One more thing, Alice,’’ he said. My hand gripped the doorknob. ‘‘I have recommended a daily encounter with the Holtz Electrical Machine.’’

*

I lay on the rubber sheet which was warm and wet with my own sweat. They are trying to turn us all into swollen pink sea creatures, I thought, staring up at a huge purple glass ball. I was instructed to press my temples into the two ‘bows’ which were there to facilitate the passage of electricity from the great glass ball. My arms were strapped to my sides, the sharp points of the ‘bows’ dug into my temples as I waited for the surge of electricity. I’d once seen an engraving depicting a young woman standing on the platform of just such an electrical machine while a man turned a crank. The caption under the print read:

‘The electrical kiss provides a very special thrill.’

The shrimp feeling was fading; now I was being turned into a baked apple, my brain going to mush.

August, 1869. It’s my twenty-first birthday and we are all gathered in the back garden of an old farmhouse my parents have rented out in Pomfret, Connecticut. My health is much improved so that I am feeling quite lively and never think of having to lie down during the day. William is basking in a hammock which he’s strung up between two pines. My friend Lizzie Boott – she and her father have a house nearby – is at her easel painting the pine trees that surround us. Father is walking about with his arms behind his back muttering to himself.

At three o’clock my mother, who has been baking, excuses herself. Moments later she appears with Aunt Kate leading a train of servants carrying the tea things and a birthday cake bombarded on top with fat cherries. ‘‘Devil’s food,’’ she explains smiling. At which, appropriately, the sky begins to darken. Father stops muttering. William stops swinging. ‘‘Look everyone!’’ cries Lizzie. William peers out from under the arm that’s been protecting him from the sun. The darkening increases moment by moment as the moon creeps across the sun. We look as if we’ve been playing ‘Grandmother’s Footsteps’. I have fallen into a lightless cave. Father is ecstatic: ‘‘Today we are blessed to witness further proof of the Divine Nature.’’ ‘‘Oh, damn the Divine Nature!’’ I cry, kicking out. ‘‘What extraordinary timing,’’ comments William. Only Mother lays her hand gently on my arm; but she cannot stop me seeing it, imbibing it, as a portent: the promise of my future eclipsed.

The electrical ‘kiss’ came with a fierce jolt.

I thought of a story by one of the new female writers in which noises were written into the text: ‘clackety clack’ for a sewing machine; ‘clickety click’ for knitting needles. Henry, I thought, would never succumb to such crudity. But I liked it. It brought the world and its sounds to life, like music.

Jolt jolt jolt … kiss kiss kiss.

‘‘Tell me about your father, Alice.’’

‘

‘But I’d much prefer to hear about your father, Doctor.’’

‘‘Oh but it is you who are here to be helped, not I.’’

‘‘And you think my father will ‘help’ …?’’

‘‘Don’t you?’’ he returned maddeningly.

I did not reply; I did not need to as my legs had begun trembling so hard they caused the floor to vibrate beneath us. It was as if Father himself had taken up occupancy in my body.

‘‘You are trembling,’’ observed the sharp-eyed Doctor.

‘‘It is true,’’ I confessed, ‘‘my father sometimes shook.’’

‘‘Shook, Alice?’’

‘‘Yes, shook,’’ I snarled, ‘‘as in ‘had the tremors’.’’

‘‘Do you imply he drank spirits?’’

‘‘Oh, please.’’

We had only just finished dinner when it began. The boys had shoved off and Mother and Aunt Kate were busy in the kitchen. That left me alone with my father. It was then that the shaking started up. Judderjudder went his head and limbs and then the rest of his body joined in. His wooden knee repeatedly hit the underside of the table sending the leftover plates and glasses skittering about. William should be here, I thought: he would interpret it as the dead come to rearrange our tableware. Or perhaps we were having an earthquake? But the quake was all in our father’s brain and bones; he had begun to gesticulate at the fireplace where ‘some damned shape’ had begun to form itself into a troupe of squat green-eyed monsters having a knees-up, cackling and hissing and spitting, until he was forced to fling his elbow across his face to avoid being the target of their ‘slime’. The word ‘fetid’ escaped his foam-laced lips. I watched fascinated, furious: ‘‘That’s what you get for eating too much cream,’’ I told him.

Aunt Kate put him to bed, soothing and petting. But there it was in his mind’s eye, the evil thing he could not get out. Have you tried an ice-pick, pater? The doctor prescribed a calming visit to the countryside; but lurking in every tree were more green-eyed fiends. Leaves, father, they are called leaves.

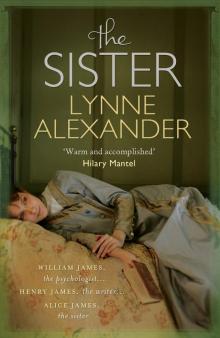

The Sister

The Sister