- Home

- Lynne Alexander

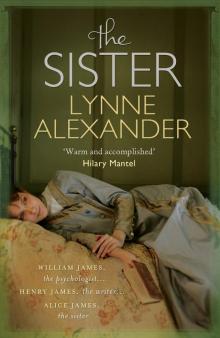

The Sister Page 6

The Sister Read online

Page 6

‘‘There is also his early history to consider,’’ he added, ‘‘about which you might or might not be aware: that Rob, as a small boy, was ‘shoved off’ onto Aunt Kate the day you were born.’’

‘‘But I was also ‘shoved off’!’’ I cried with a pummel to the mattress.

‘‘Ah.’’ He did not know of it, but now that I had brought it to his attention he supposed Aunt Kate had picked up many pieces – ’’and you, Alice, were alas the last James ‘piece’.’’

‘‘The puzzle piece that wouldn’t fit,’’ I grumped unattractively.

‘‘But Henry – to return to the subject of Rob’s marriage – everything you have been telling me about Rob is entirely from his point of view. Imagine what it must have been like for poor Mary, abandoned and left alone with a child.’’

‘‘Ah Mary … indeed,’’ he allowed.

‘‘I mean, poor Wob!’’ I lisped, my voice like one of Macbeth’s witches sweetened with blackstrap molasses. Surely – I was convinced of it – he was the problem, he was the selfish, restless, irresponsible one. How else could he go galivanting off to Egypt, leaving Mary with the children; and before that, checking into an asylum, for goodness sake, where he might rest and be taken care of? Selfish selfish Rob!

Henry recoiled, which shocked and frightened me. Suddenly I saw myself through his eyes, how merciless I seemed, how unforgiving. I heard my father’s words from long ago: ‘‘How hard you are, Alice!’’ Of all people I should understand about nervous illness. But I was like an animal who, catching sight of itself in the mirror, springs to the attack because it loathes what it sees. I shivered, aware of Henry pulling away from me, fearing an awful gap opening between us to swallow up our ‘perfect mutual understanding’.

I hugged my knees to my chest. ‘‘Mother is dead,’’ I said in a small, sawdusted voice. ‘‘Yes,’’ agreed Henry placing a restraining hand on my knees and another on my shoulder. I’d begun rattling all over like a pane of glass. ‘‘Are you cold, Alice?’’ I could not reply. He closed the window but the rattling did not stop. Dope. What had I been thinking? The truth was I could never live up to my mother’s example: such shine does not transfer. I’d supposed myself managing the house, the servants, the meals, the workmen, the visitors just as my mother had. But she had gone about her domestic business so efficiently we were hardly aware of her; whereas I, Alice, had had to point here and there, saying I did this and I did that, like a small girl fishing for a pat on the head. I began making a drilling noise through my teeth while poking a hole with my finger through the bedclothes.

‘‘Alice …?’’

Something was driving me on in my wretched pursuit of what Henry would have called ‘the whole picture’; only in this case I risked losing Henry himself. I did not care. Oh, let the gap widen, I thought, let him never speak to me again.

‘‘Henry,’’ I imparted, ‘‘our Mother was not perfect, you know it. She was also meddlesome and controlling.’’ A laugh erupted, painful as a bark. ‘‘She wanted you to stay close, she was always intruding: were you eating well, getting sufficient sleep, spending too much money, or not enough? And what of the ‘life of the affections’? On and on it went, Henry. Don’t you see,’’ I pursued, ‘‘we have been damaged. Can you not feel the vibration of her selflessness and devotion, on all of us, like a dentist’s drill?’’

Henry threw out his lip, pale as the jug beside us. My brother, I understood, who claimed to indulge in ‘fictional verities’, feared the unstoried, unembroidered. Call it the bald truth, if you dare. Off he trotted to fetch me a hot water bottle. The heat was comforting but my Mother’s presence pressed in upon me. Give all but ask nothing, that was her message; or was it command?

‘‘But I do ask, Henry,’’ I cried urgently, as if she’d actually spoken: ‘‘I do.’’

‘‘For what do you ask, Alice?’’ he asked.

I could not explain. I feared I wanted too much, which made it even more sickeningly impossible. Finally I blurted out:

‘‘I can never hope to be like her.’’

‘‘No,’’ he agreed,’’ smiling benignly: ‘‘You are yourself, Alice,’’ he pronounced, ‘‘that is more than enough.’’

After another pause he announced, domage, he must return to England. He had already written to his friend Lord Rosebery saying he was ‘desperately homesick’.

‘‘Home-sick? But Henry,’’ I objected, ‘‘our home is here, across the ocean. As for London, you recently described it as ‘a mighty-flesh-eating ogress’.’’

‘‘Ah, but the poor ogress is only human.’’

‘‘But doesn’t the heart harden in her company?’’

‘‘On the contrary: she teaches people their places, breaks reputations, tears out their hearts.’’

I leant forward: ‘‘And that is a good thing?’’

He believed it was.

‘‘Henry,’’ I dared ask, ‘‘do you remember that letter you once showed me?’’ He nodded. It had been from our mother: ‘It seems to me, darling, you must need this succulent, fattening element,’ she’d written, urging him to return to the bosom of the family. But the ‘succulent, fattening element’ would have trapped him like a pig in a vat of its own lard. He’d had to get away, escape into the arms of his ogress-mistress, across an ocean at least.

Now, I thought, I must let him go.

As he bent towards me I observed his lips, so like my own, bowed in the middle and downturned at the corners, but just that bit fuller and less pursed-up. They brushed my forehead: ‘‘Alice, you will keep me informed about Father. And take care of yourself, of course.’’ He did not look back, quickening his pace down the creaky new stairway as if fearing I and my illness would come crawling after him, enormous and engulfing; while I lay there thinking how some of us must hold on for dear life while others must let go or perish.

After he was gone I wrote a story about a daughter who nurses her ailing mother. One day the daughter goes to the market and purchases a pig’s head which she carries home tenderly in its slippery white beribboned parcel as if it were a newborn baby. Back in the kitchen she dismisses the servants: she must make the stew herself. It will be her masterpiece. As she chops up the various bits – snout, ears, eyes, cheeks – she tells herself, ‘Mother will just die for a good rich pork stew.’ And she does. Die. It was not Art, it was illness. I destroyed it, of course. The doctors were right: I must not write.

Eight

‘‘Here comes another death scene,’’ I hissed outside father’s door. ‘‘Hush, Alice,’’ scolded Aunt Kate, ‘‘do not disgrace yourself with irreverence.’’ She was carrying a washing bowl filled with some disgusting liquid. ‘‘But I am the reverent one,’’ I objected. It was my father who was claiming to be dead before his time, and that was surely a crime against Life. Our father who art not yet in heaven yet not quite on this earth, warm in his bed but yearning to go, reaching with his pajama’d arms towards his vision of paradise; an ecstatic aged child anticipating his finest Christmas present ever: Take me.

By this time we’d returned to Cambridge. My father had had enough of rocks and sea, he said; not to mention the gulls wheeling about ululating outside his window. ‘‘Mary! Mary!’’ he’d begun wailing, convinced the seagulls were his dead wife. Time to go, I announced miserably, starting to close up the cottage. The slam of shutters and doors, sheets ballooning over beds. And the new house’s promise? Spilled like paint. All that clean glass, those waiting drains. Had I called it ‘my creation’? Fool.

He refused all doctors but the homeopathic Dr. Ahlborn, who could find nothing organically wrong. Father hooted like an owl invoking The Unknowable Reality Behind Phenomena. Ahlborn coughed, lamely prescribed rest of body, stomach and brain. Aunt Kate tried tempting him with thin gruel, but he would not be tempted. ‘‘Mary, Mary,’’ he wailed again while I silently supplied the quite contrary.

‘‘He talks only of joining her,’’ said Aunt Kate: ‘‘I fear

it won’t be long.’’

I let myself into his sickroom. ‘‘Shall I close the curtains, Father? The sun was directly in his eyes, but he would stare it down. In it he saw the fiery gaze of his opponent and friend, M. le diable – for without him there would be no chance of transformation. My father, fierce yet soft-headed as ever. ‘The age of the severe and remote patriarch is over,’ he’d once written: ‘a more appropriate symbol of divinity is the maternal, the benevolent.’ Perhaps, Father, I thought, you should have been born a woman?

‘‘But what exactly does your Father do, Alice?’’ our cousin Minny had once asked. To which I’d replied, ‘‘He doesn’t do, he thinks.’’ ‘‘About what?’’ I reeled off, ‘‘Philosophy, theology, morality’’ – the words flying out detached from meaning. I selected one of Father’s books to show her – Substance and Shadow; or Morality and Religion – but when she opened to the title page there was Henry’s woodcut of a man beating a dead horse. ‘‘Oh dear,’’ she’d cried, shutting the book and putting it from her. Years later William, less gruesome but equally cruel, would summarize Father’s life’s work as: The monotonous elaboration of a single truth.

Poor Pater, I now thought: to have had two such brilliant sons!

But there were practicalities to attend to. ‘‘What should you like done about your funeral, Father?’’ I asked. He sat up, shocked into lucidity. ‘‘Tell the vicar to say only this: ‘Here lies a man who has thought all his life that the ceremonies attending birth, marriage and death are all damned nonsense’. And don’t let him say a word more. Promise me, Alice.’’

‘‘I promise, Father.’’

His eyes shadowed over.

‘‘What is it, dear?’’

‘‘Henry,’’ he began muttering: ‘‘HenHenHen … .’’

‘‘It’s allright,’’ I soothed. ‘‘I’ve telegraphed him. He’s boarding ship as we speak. He plans to bring William with him.’’

My father was clearly agitated: ‘‘What is it, Father?’’

‘‘No Woom.’’

‘‘No …?’’ I put my ear closer to his mouth.

‘‘No Wi-wm.’’

‘‘No William?’’ I guessed correctly, to his relief. So that was it: William was not to be summoned. William the Sensitive must not be made to witness the pater’s confusions, his arms waving about like twigs in a gale. William the Susceptible must be spared his father’s descent towards death. It smelled. It was not nice.

‘‘And Henry …?’’ I asked. He blinked. Yes, Henry may come. And Rob and Wilkie? Let them all come. ‘‘I am dead, Alice, I am in Glory,’’ he intoned. He made a noise like a valveless trumpet trying to play a passage from Bach or Handel. Suddenly he took my hand and pulled me closer: ‘‘An urgent message before I depart this world,’’ he whispered. I put my ear to his dry chapped lips, my heart unfolding ready to receive the gift. ‘‘I have such good boys,’’ he announced, clear as anything: ‘‘ – such good boys!’’

I tried to stifle the whimper but it would out, along with the barely audible cry, ‘‘What about me, Father? What about me?’’

I am in my father’s study. I am eight years old. The boys are away at school. I, a girl, am being treated to a different kind of lesson. ‘‘My darling girl,’’ Father calls me. The smell of books – paper, ink, leather – of the roses my mother has placed on the table beside him; dust motes in a sunbeam. I am alone with him, so I must be special. ‘‘You are goodness personified, my Alice,’’ he tells me: ‘‘Do not ever forget it. It is a gift, natural goodness, a virtue that does not have to be learned.’’ He places his hand on my head as if personally passing his blessing onto or into me. I feel the heat of his cupped palm, then its hot pressure forcing me down: You are goodgoodgood. ‘‘But I want to learnlearnlearn!’’ I cry: ‘‘I like to learn!’’ I jackknife so that his own hand – the hand that has been holding me down – flies back slapping his face and knocking his spectacles off. A bead of blood appears at his brow, a cut from his own heavy gold ring. I must not find it funny, or think serves you right. I have caused it to happen.

I run to my mother who sprinkles a damp cloth with rosemary oil; I grab it and run back to my Father and dab at the wound. When it’s free of blood – it was only a scratch, after all – I paste a tiny plaster over it. After that I scrabble for his glasses, which I find under the table unbroken, and place them back upon his wise old nose. It takes a moment for him to focus, as if he’s forgotten who I am; then, remembering, looks pleased, for his point has been proved: ‘‘You see, you are another ministering angel.’’ He holds me by the waist and jiggles me from side to side. Goodgoodgood.

No I am not, I want to crow, biting my tongue.

Instead I employ a rational argument. ‘‘But I have heard you telling the boys that evil leads to goodness since it is the struggle that marks the path to divinity.’ Therefore do I not have to be bad first before I can arrive at true salvation and goodness? If we, I, do not struggle, then we, I, account for nothing.’’

My father places me squarely between his legs. ‘‘Ah,’’ he sighs, ‘‘My little heiress of the paternal wit.’’ I find I am dismissed. Later as I lie awake in bed, I try reasoning to myself: ‘I have hurt him. I have been bad. But then I made it better so I am good and saved.’ But that only confuses me more, for it leads to the conclusion that I will grow up to be a man.

I left him to search out my sister-in-law Alice. ‘‘He is adamant,’’ I reported, ‘‘that William not be summoned back: should we obey?’’ She thought that we should. ‘‘It is no doubt best for your Father. As for William,’’ she added without a touch of irony, ‘‘he prefers to be out of the country in moments of stress.’’ She hugged her stomach. Strange to say, my brother had been called away ‘on professional business’ a week before the birth of their second son Billy only a month before. Which left me musing to myself, Where do you hide, Willie, while your Alice is laboring with child and your Father with death? Is there a secret place where their pleadings cannot get at you, the blood not seep into the cracks of your flesh? Is that how you know so much about the split-off self? How we all know, whether or not we smell the smells and suffer the visions?

‘‘Where is he now?’’ I inquired.

‘‘Oh, he’s on sabbatical in Oxford, working on a theory of the emotions.’’ A theory of the emotions? Ah, I thought, an Oxford college, perfect: the life of a cosseted student. ‘‘It’s for the best that he stays put to complete the writing otherwise he will be impossible. Besides, it will distress him too much, he’s been having episodes of blurred eyesight.’’ Aunt Kate concurred. Having William fussing around would only make things worse. ‘‘We’d have to nurse him as well. It would not do.’’ We struggled to keep our faces on straight.

Nine

A trickle of embalming fluid had escaped my father’s lips. As I plucked my handkerchief from my sleeve and reached towards him I felt Aunt Kate’s hand close firmly around my arm. ‘‘What on earth do you think you’re doing, Alice?’’ ‘‘Cleaning him up,’’ I replied, pointing: ‘‘He’s … leaking.’’ She snatched the handkerchief. ‘‘You did not see that.’’ She peered in. ‘‘Besides, it has stopped.’’

The third day of his death. Floor lamps had been placed at either end of the coffin in which he lay like a life-sized bewhiskered doll. Beneath the myriad of flowery and perfumed scents you could detect wax and chloroform, and death of course. Yet he himself appeared more peaceful than in life. He has escaped, I thought, just as someone remarked, ‘‘I guess if Abraham Lincoln could be embalmed, so could Henry James Senior.’’ And another: ‘‘Well, after all, he is one of Boston’s famous sons.’’

The affair would have suited Prince Albert himself with its coffin photographs, memorial cards, door wreaths, drapes – all in black of course; not to mention the black-bordered front-page obituary in the Boston Globe. (My mother, by contrast, had stipulated her funeral and its aftermath should be as simple and unfussy as possible, ca

using the family the least amount of bother.)

Eventually he was removed and taken to the family plot where, in due course, a modest mausoleum would be erected. My only fear, which grew as they began lowering the coffin, was that his demons – bats, albatrosses, raptors, wolves of course – would escape and latch onto me, circling my throat like some fantastical zoological necklace. We are a gift from your father so you can struggle too and achieve goodness. …

A cold, snow-infested January day. We held onto our hats. According to my father’s dying wish, that he be spared the usual Unitarian ‘claptrap’, the minister read from one of my father’s own theosophical tracts laced with mad Swedenborgian notions. But then we got the ‘damned Unitarian claptrap’ too. I tried not to picture him spitting with fury in his coffin, as he surely would be, or I would lose my composure. Aunt Kate and William’s Alice were gripping me, one each side, to stop me throttling the minister – which I was sorely tempted to do. ‘‘The bare trees are busy applauding bony death,’’ muttered I.

William’s letter from Oxford – to be read out to father on his deathbed – had arrived too late. I’d been tempted to send him a telegram saying TOO LATE WILLIE BAD LUCK – but he might have thought it somewhat tasteless.

Henry did not arrive in time either. I’d left a note for him at the shipping office: The funeral is today, we have gone ahead, there seemed no use in waiting for you as the uncertainty was so great. As we stood beside the grave I kept thinking his cab would come rattling through the gates of the Cambridge Cemetery and he’d appear like the hero in a mushy story out of Girl’s Own. He did not. He arrived late that night. ‘‘All over,’’ I sang. He tilted against me as if he might collapse and I felt the vibration of a groan pass through his chest and into mine.

The Sister

The Sister