- Home

- Lynne Alexander

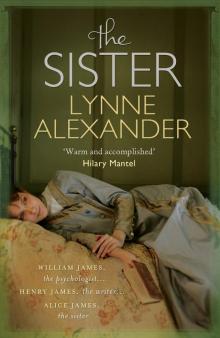

The Sister

The Sister Read online

Lynne Alexander was born in Brooklyn, New York and moved to Britain in 1970. She became a professional harpsichordist before turning to writing in 1980. She has since published five novels including the widely praised and translated Safe Houses. Her work as writer-in-residence at three hospices is recounted in two volumes of poems. She also taught on the MA program in Creative Writing at Sheffield Hallam University. Now retired, she lives in an AONB in the northwest where she continues to write.

About The Sister

It is a warm and accomplished work of sympathetic imagination. I felt myself, as I read, wholly absorbed into Alice’s painful but fascinating interior life.

Hilary Mantel

Praise for Safe Houses

Gerda is a phenomenal character – pure life force. In spite of its grim theme, the book is funny and rich in imagery.

Clare Boylan

This is, in the best sense, a subversive achievement … It is hard to think of recent novels on this modest scale which contrive to entertain with such a bewitching diversity of resource.

Jonathan Keates, The Observer

Its extravagant language, clever word-play and balancing act between humour and the grotesque mark it out from other recent fiction on the theme of the Holocaust and emulate the masters of fantasy Gunter Grass and Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

Deborah Steiner, TLS

The extravagance and richness of Lynne Alexander’s language find their fullest expression in transforming Brooklyn itself into a nightmarish fairyland, where gingergread ovens wait for innocent little girls, and the wicket flourish and fatten on Windtorte.

Elaine Feinstein

Safe Houses is a brilliant and disturbing novel …

Julian Alexander, Literary Review

There is nothing safe about this audacious first novel …

Washington Post Book World

Alexander has fashioned a work that is layered in its moral complexity, sensitive and humorous in its treatment.

San Francisco Chronical

Praise for Adolf’s Revenge

Lynne Alexander’s exhilaration with words carries her and the reader along … Angela Carter with a kinder heart plus jokes. And good ones at that.

Fay Weldon

Wonderfully fanged and fetid.

The Independent

Alexander’s toxic narrative, full of pseudo-biblical curses, lends a rich comic patina to the proceedings.

The Sunday Times

A tale of power and manipulation that deals in raw enotions and pokes run at predictable happy endings.

The Times Weekend Saturday

Praise for Resonating Bodies

Skilfully and in the most entrancing prose, she makes the reader accept the instrument as a voluptuous woman of unfading beauty.

Miranda Seymour

Lynne Alexander, who once earned her living as a professional harpsichordist, has written a persuasive and erotic love story about a superior fiddle.

Philip Howard, The Times

Alexander raises questions about changing fashions in sex roles, musical style and how far art justifies the sacrifice of personal and political commitments.

Jane O’Grady, The Sunday Times

Part of Alexander’s achievement is to show us the need for ‘irrelevant’ comforts in a ‘hell-bent century’ and to convince us that at least one half of life is fantasy.

Anna Vaux, The TLS

Praise for Intimate Cartographies

Lynne Alexander has chosen the most difficult of subjects, the death of a child. She has treated it with sensitivity and wit, manic levity and the utmost respect, and has created something quite haunting.

Carol Birch, Independent on Saturday

The core of this lively, dense and at times infuriating novel is Magda’s relationship to her dead child, and this I found very moving indeed.

Paul Binding, The Independent on Sunday

Loved Intimate Cartographies … The map of grief was utterly compelling … the glimpses of Molly were perfect … Most of all, I liked the tone of the writing – sharp, witty, clever and requiring absolute attention so as not to miss a single nuance.

Margaret Forster

Also by Lynne Alexander

Fiction

Safe Houses

Resonating Bodies

Taking Heart

Adolf’s Revenge

Intimate Cartographies

Poetry from hospices

Now I Can Tell

Throwaway Lines

Non-fiction

Staying Vegetarian

THE SISTER

LYNNE ALEXANDER

A novel based on the life of Alice James

First published in Great Britain 2012

Sandstone Press Ltd

PO Box 5725

One High Street

Dingwallv

Ross-shire

IV15 9WJ

www.sandstonepress.com

All rights reserved.

No part of this production may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

Editor: Robert Davidson

Copyright © Lynne Alexander 2012

The right of Lynne Alexander to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

The publisher acknowledges support from Creative Scotland towards publication of this volume.

ISBN (e): 978-1-905207-81-7

Cover by Rebecca Pickard, Zebedee Design, Edinburgh

Ebook by Iolaire Typesetting, Newtonmore.

Contents

PART 1

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

PART 2

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-one

Chapter Thirty-two

Chapter Thirty-three

Chapter Thirty-four

Chapter Thirty-five

PART 3

Chapter Thirty-six

Chapter Thirty-seven

Chapter Thirty-eight

Chapter Thirty-nine

PART 4

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-one

Chapter Forty-two

Chapter Forty-three

Chapter Forty-four

Chapter Forty-five

Chapter Forty-six

Chapter Forty-seven

Chapter Forty-eight

Chapter Forty-nine

Chapter Fifty

Chapter Fifty-one

Chapter Fifty-two

Chapter Fifty-three

Chapter Fifty-four

Chapter Fifty-five

Chapter Fifty-six

Chapter Fifty-seven

Chapter Fifty-eight

PART 5

Chapter Fifty-nine

Chapter Sixty

Chapter Sixty-one

Chapter Sixty-two

&

nbsp; Chapter Sixty-three

Chapter Sixty-four

Chapter Sixty-five

Chapter Sixty-six

Chapter Sixty-seven

Chapter Sixty-eight

Chapter Sixty-nine

Chapter Seventy

Chapter Seventy-one

Chapter Seventy-two

Chapter Seventy-three

Chapter Seventy-four

Notes

Acknowledgements

Bibliographical Sources

‘What could justify a life for Alice –

and perhaps for all the Jameses –

was not so much the living of it as the writing about it.’

Linda Anderson,

Introduction: Alice James, Her Life in Letters

‘… her tragic health was in a manner the only solution for her of the practical problem of life.’

Henry James, in a letter to William

‘Delight becomes pictorial

When viewed through pain, – ’

Emily Dickinson

I. BOSTON, USA

(1878–1884)

One

My father’s curse went something like this: ‘‘I fear, my dear Alice, it is the natural inheritance of everyone capable of a spiritual life to wander alone in an unsubdued forest where the wolf howls and the birds of night chatter.’’ Sometimes ‘the unsubdued forest’ became ‘a clanging rookery of hell’, but either way his meaning was clear. Well thank you for that benediction, pater.

The year is 1878 and I am about to be thirty years old. I sit at the small corner writing table with my eyes facing forward as if mesmerized. On the desk before me lies an assortment of papers which I have divided into three: (1): engraved wedding and engagement announcements from Sara Sedgwick and Annie Ashburner – the last of my single allies to desert me for the enemy; (2) a letter on onionskin from the Society to Encourage Studies at Home (signed by Katharine P. Loring); (3) a draft of an essay by my brother William entitled ‘The Hidden Self’. Tucked inside it I have discovered another engraved wedding announcement: his own. I freed it from the essay and placed it among the others in pile one. My other brother Henry’s newly published nouvelle, Daisy Miller, occupies a space of its own.

My father, meanwhile, sat at the desk in the middle of the library facing the garden. He would be thinking hard or pondering his Swedenborg, the philosopher who claimed, among other crackpot notions, that the great toe communicates with the genitals. Blake, who was also a follower, had done a self-portrait showing his body flung back while a flaming star descends towards his left foot. I could not resist swiveling round to observe my father’s foot. It waggled beneath his desk. But I must not snigger or he would ask me to recount the reason for my amusement.

‘‘Did you speak, Alice?’’ he asked, without turning to look at me.

‘‘I did not intend to,’’ I replied, my words snapping like sticks around the hilarity that threatened to burst out.

Then I remembered William’s announcement.

In my bureau upstairs was a pile of letters from William tied up with a blue ribbon: blue for clarity and hopefulness. The letters had been addressed to: ‘You Lovely babe’, ‘Charmante Jeune Fille …’.; inside they told me I was ‘sweet lovely delicious’ but ‘must be locked up’. To my face he’d told me he ‘longed to kiss and slap those celestial cheeks’. What had he meant, that I should be made love to or punished, or both?

The wall before me was papered in brown with splodges like gravy spills through which he appeared smiling with his handsome face: William, brother; his voice crooning and melodious: ‘Dearest little sweetlington, beloved beautlet … my grey-eyed doe … Now, can you guess what I have to tell you?’

‘‘What is it, William, what?’’ The pulse pounds in my temples quick and hot reminding me how wicked I am and deserve to be smacked and locked up &etc. ‘Guess,’ he says, dangling his metaphorical ball of string.

‘‘Please, William …’’. Must I meow? reach out my paw?

‘‘Kiss my hand, my little beauty.’’

I do as I am told.

‘‘Now then, I have decided to do the usual thing.’’

I drop the kissed hand. ‘‘The usual …?’’

‘‘I am to be married, Alice . . . and to another Alice!’’ Someone it seems is slapping him on the back forcing the air out of him along with the hearty words. I’d always had a weakness for having my friends married, but my brother was a different matter. ‘‘But you promised to marry me, William. You vowed, you threatened – I have the letter – if you couldn’t marry me you would kill yourself.’’ I have the evidence; I am quite rational. I go on: ‘‘You even wrote a ‘sonnate’ in honor of me. You sang it in the parlor, Willie, you sang:

Since I may not have thee,

My Alice sweet, to be my wife,

I’ll drown me in the sea, love,

I’ll drown me in the sea!’’

‘‘Were you serious, Willy, or simply trying to turn me into a scrambled egg?’’ But he does not reply. He has retreated back into the gravy spills with his intended.

Alice meet Alice.

My mother came running. ‘‘What on earth is going on in here?’’

My father saw in my shaking body the proof of his prediction. He rose to announce, ‘‘I fear she has inherited my affliction: ’Tis the obscene bird of night. It has begun its chattering.’’

‘‘Chatterchatter,’’ said I.

My mother held her temper. ‘‘It is not night,’’ she told my father tightly. ‘‘It is neither a wolf nor a bat, it is your daughter Alice. She is in trouble.’’ He shrank before her, and who should blame him. Meanwhile I had crashed to the floor dragging down books and papers, yet part of me could still make out what was going on around me. William, you see, had written about this phenomenon: The only difference between me and the insane was that while I suffered the horrors and suffering & etc. the other part of me played doctor, nurse and straight-jacket. It was very tiring.

But William’s letter had contained another message:

‘‘Let your soul grow wings, Alice,’’ he’d written. Yes, that.

grow wings grow wings

My poor heart feasted. And there was more:

‘‘Let your voice be musical and full of caressing … let every movement be full of grace … my Alice, you have no idea how lovely you will become …’’.

Even as my teeth knocked within my silly head I felt his words rising me up. I would not need a hot-air machine however as I would soon grow wings to fly …

‘‘But …’’ he’d added. I pictured him finger-in-air.

‘‘ ‘But’ what, William?’’

‘‘But only very short ones!’’

Short wings! haha!

The ball of string had been cruelly retracted. I reached up. My nails gripped paper and tore, my arm struck out. Fury ripped through me: I will make his head roll like a ball of string! But he was not there to receive his punishment so I turned my wrath against the benignant pater with his silver locks, nearly knocking his innocent block off; and when that was foiled I tried flinging myself from the window. I panted like an animal for breath then tried to hold it until I was no more. I could not tell if I was dry or drowned but that I was sinking, my limbs making swimming motions, while over my flailing body my parents argued about what to do with me. My father was convinced it was the wolves come to get me, wooo-hooowoh. Well, I thought with my ‘observing’ brain, at least it’s a change from the chattering birds of night!

There would be a struggle, Father predicted, but I would be victorious.

‘‘And if she is not?’’ Mother inquired icily.

Later, my father knelt at my bedside. Clunk, came the sound of his peg-leg hitting the floor as it bent. Perhaps he will pray for me, I thought.

Suffering brings love, tenderness, forgiveness …

Sometime in the night I dreamed of my father as a boy heating a balloon to make it fly. Up he rises lifted by t

he heat of the turpentine soaked ball of tow … but the fire soon spreads simltaneously down to his leg and up to the silk canopy, rising above him like a great flaming sky-rose. Then, in the way of dreams, my father transforms into me with wings shrunk down to wagging stumps (grow wings! but only short ones!). And so I fall to earth, my head divided from my neck, my arms and legs all in a heap.

Poo-wor Alice.

William and Henry came to see me. They leant over me like a pair of bearded bookends. ‘‘I am not a book,’’ I said, pushing them gently apart. I had no book inside me, I had been emptied out. It felt quite restful, especially in my brain; it meant I did not have to think. Besides, I’d managed to control my muscles and their murderous twitches; otherwise I might have been tempted to crack the two balding heads together like a pair of coconuts.

But Henry was saying something. ‘‘You have heard that William is to be married?’’ he asked gently. William looked away. I nodded, trying not to snarl like a wolf and bite his neck. You were going to marry me. But there was Henry saying in his smoothing-iron voice: ‘‘The future bride, we gather, is also called Alice: Alice Howe Gibbens.’’ At this, William The Sinner bows his head. ‘‘I have been ill,’’ he wails: ‘‘a spoilt child, an errant soul – but she will be my cure.’’ Oh, for goodness sake! I long to squeeze him until all the disgusting syrup of figs runs dry and all the maudlin furniture coated in it falls out, clunk. Henry meanwhile wisely attends to a hangnail. William, having no idea he is being absurd, raises his head.

‘‘She is an angel if ever there was one.’’ Amen.

‘‘Alice,’’ I tried. Alice meet Alice.

But now it was Henry’s turn. Henry, ‘playing it’ lightly, chose his moment. ‘‘What on earth,’’ he asked, ‘‘will we call you for distinction’s sake?’’ I was no help at all, so then he began entertaining the various possibilities himself: ‘‘William’s wife could be ‘Mrs William’ or ‘William’s Alice’, or even ‘Mrs Alice’; while you could be ‘sister Alice’, or ‘our Alice’.’’ It was the only time I had known him before or since to have been less than exquisitely sensitive. But then he redeemed himself by adding warmly: ‘‘Of course you will always be ‘my Alice’.’’ Dear Henry. My mouth arranged itself, my chest rose and fell. There were more-or-less even beats within. I observed these things with interest but felt nothing. My mother came up behind Henry, ever her favorite, and laying a hand lightly on his shoulder peered down at me. Then I heard her say – having somehow managed to wipe from her mind all of the previous scene: ‘‘Is she not the sweetest invalid in the world?’’

The Sister

The Sister