- Home

- Lynne Alexander

The Sister Page 3

The Sister Read online

Page 3

One day William’s Alice presented me with a soft boiled egg. ‘‘Why,’’ I cried, ‘‘you have brought me the sun!’’ Only I couldn’t swallow it, having noticed a perfect pearl about to fall from one of her nostrils and land upon the egg’s head. I had a sickening vision of William kissing that viscid nostril but just then she pulled her handkerchief from her sleeve and staunched the drip. She was recovering, she explained, from influenza assuring me however that she was no longer contagious. I said I was glad of that adding, ‘‘I hope it will go lightly with you and not lead to suicide.’’ Her hand flew to her throat. ‘‘Suicide,’’ she yelped, ‘‘whatever can you mean?’’ I explained the papers had been full of stories of ‘the exaggerated American response to the disease’ culminating in a ‘rash’ of suicides – had she not heard of it? ‘‘No I have not,’’ she replied allowing the hand to unclaw itself but her angel’s eyes grew darker and she did not visit me for a long while after that. Nor did William for that matter, though he wrote largely of his ‘imbedment in the soft domestic bosom’. His Alice had saved him: ‘I was a diseased boy,’ I read, ‘whom she has lifted from the dust and transformed into a man’. Well, I thought, picturing her raising him up and dusting him down, You cannot do better than that, Willy. I also understood that his ‘marriage-cure’ depended on his keeping his distance from the ‘neurotic’ unhappiness of his bedridden sister Alice. ‘Give my love to Alice,’ I wrote, ‘but don’t let her know you address me as Dearest Alice,’ I advised, ‘or it may complicate our relations.’

Doctors rumbled and mumbled over me: nervous paralysis … prostration … female hysteria … prescribing rest and more rest and custard and rest. ‘‘But surely, Doctor, I may be allowed to read and write?’’ ‘‘Write? certainly not!’’ Writing was bound to excite the imagination in morbid ways, though letters might be permitted. I was of course being managed and defined, yet I gave myself up to their inferior wisdom letting them believe I played into their hands. Was I not after all the sweetest invalid in the world?

Only Henry’s letters continued to amuse me with their talk of London life with its ‘inscrutable entrees’ and ‘feeble tinkles of conversation’: chatterchatter. Yet I preferred ‘horrible’ London over ‘aesthetic’ London: low neighborhoods at night with numerous poor wretches reeling home to squalid dens or rolling across the roadway and cutting themselves till the blood flowed. I lapped up such descriptions along with bulletins detailing the state of his bowels, back and stomach – which Aunt Kate thought should really be marked private.

Time passed. Picture a Rumpulstiltskin-like figure stomping along my prone body with his little leaden boots, marking the seconds. Nor could I spin straw into gold. In other words, it passed slowly, painfully and reproachfully.

At some point Henry (who could make time pass in his stories by sheer sleight-of-hand) appeared in the flesh (and quite meaty he looked too). He’d returned from Paris to see his publisher and friend Dean Howells. Mere pretexts, he insisted, to see me. Dear Henry. He held my hand and asked after my health. ‘‘My health?’’ I was beginning to think communication by letter was far easier. ‘‘I do not have such a thing: I am as you see me.’’ His cheeks wobbled like a dog’s. I patted his hand therethere, my dry skin touching his moistness, his solidity. I am holding Henry, I thought: a handful of Henry. ‘‘Tell me about you,’’ I encouraged. He complained about Dean who’d insisted on delaying the complete edition of The American until all the serialized copies had been sold out. ‘‘But it is selling well?’’ He nodded. I said how pleased I was, which was true. Then he announced his plan to settle in London. I said it sounded damp. He patted my hand again, turned it over, stared into it and was gone.

*

After Henry left I took up my writing things and began a story about a chamber pot. But a word, before I go any further, about my writing – or rather scribbling. Henry wrote, I scribbled; that was how it was. And yet. The question that occupied my mind – assuming I was to continue – was what to write upon? Paper was the obvious thing. But what sort? The local stationers’ had provided a list that went on for several pages describing various weights and qualities of papers. I was tempted by onionskin – thin, slippery and transparent as skin itself – but far too noisy. And then, paper of any sort was problematical in that it proclaimed its right as the correct material to be written upon thus making it far too official, too professional a medium for a nobody like me. I would have to be certain that what I had written was worthy of the stuff it was written upon. Which I would doubt. At first I didn’t doubt. At first I thought my efforts rather good. But when I read them I decided they’d ‘gone off’ like sour stews.

Yet if not on proper paper, what then?

On one occasion I asked Aunt Kate to collect an assortment of leaves for me. ‘‘What sort of leaves?’’ she wanted to know. ‘‘Large, soft ones,’’ I replied, ‘‘not too brittle yet not too soft: large-leaved limes, sweet chestnuts, maples.’’ Then she wanted to know what they were for so I explained I had decided to study the pattern of their veins. ‘‘I see,’’ said she suspiciously.

But the pen tore through the leaves.

There could be a notebook, of course, one of those cheap, roughly-sewn school notebooks with lines or even without lines. Each tale would be self-contained. Having completed one, I could begin another. But what if I could not complete a tale? There would be the evidence, clear as an account book showing I had failed to pay my debts. Failure after failure; lined or unlined; stamped or unstamped.

There could of course be a large blank book: thick and leather-bound, which could easily be disguised as a diary; indeed, could actually be a diary with a lock and key to ensure its privacy. Filled it would contain a collection of my tales; in other words it would then have become a book. Which must not happen, I saw, for it would amount to announcing myself as a writer which I could not do. I dared not author a book even if I was capable of filling one. The distinction must be made.

There was only one solution left. I would write on scraps: the backs of discarded envelopes, shopping lists, bills of sale, the reverse sides of letters. When I had completed a tale, I would simply gather up the pieces and ‘file’ them in a large manila envelope which I would slip under my mattress. When it became overful and lumpy, I would start another manila envelope. The solution pleased me.

But about the chamber pot. My preoccupation with such a thing must have seemed to the New England snowdrop souls round about somewhat Rabelasian. It would not do, therefore to make it the subject of a tale. I mean, imagine Henry writing about a chamber pot. I could not. But then came this owlish message: Do not mock chamber pots, Alice, they speak truth.

Four

One day in late winter my old friend Sara Sedgwick came to see me. She had gone over to England in ‘77 to visit with relatives in Yarmouth and had caught herself a husband. ‘‘I hear the herring are plentiful again this year,’’ I said spitefully: ‘‘perhaps I will go and fish myself one.’’ Her eyes popped. ‘‘Alice, William Erasmus Darwin is a banker not a herring.’’ ‘‘No, of course not.’’ I did not repeat Henry’s description of him as ‘gentle, kindly, reasonable, liberal, bald-headed, prosaic’ & etc.

‘‘So, Sara Darwin, nee Sedgwick.’’

She scooped like a swan. What must it be like, I thought, to cast off one’s original name and slip into a new one like some off-the-peg garment? What if it pulled under the arms and across the back? Or was so loose and baggy that you felt lost inside it? Of course alterations could always be made but … was not marriage the occupation of occupations? It was, if nothing else, as Henry called it, ‘the usual thing’. But she was looking droopy and miserable.

‘‘Well?’’ I asked.

‘‘Well what, Alice?’’ Her attempt at defiance.

‘‘You know very well,’’ I replied, adding, ‘‘And how is it being a wife?’’

‘‘Ah, that.’’ She made a sour little face: ‘‘The Darwins are thick as thieves, as you

can imagine.’’

‘‘Can I?’’ I supposed I could: the men with their cigars huddled around the fire while the wives stabbed at their canvases like great spotted woodpeckers at dead branches. But William Erasmus, the new husband, would not abandon his Sara for long. What would it be like to be allied with another against the rest of the world? Once I thought I knew of such a thing but now I could hardly imagine it.

She was showing me a photograph her father-in-law had given her: not the usual cameo of a human head but a frog leaping off a leaf. ‘‘It’s a Coki Tree Frog,’’ she explained: ‘‘Mr Darwin says according to Indian folklore the sound of this frog is the voice of springtime. It was regarded as a symbol of good fortune and – she paused meaningfully while touching her barely-swelled stomach – ‘‘fertility.’’ Ah. I allowed the news to register before pronouncing with some sincerity: ‘‘Well congratulations, Sara Darwin.’’ She blushed a deep rose madder then perversely looked annoyed: ‘‘For what?’’ she asked, opening wide her doll ribbon blue eyes. I thought her disingenuous or dim, or possibly both, but then it dawned she was quite right to be provoked. That one should be congratulated merely for one’s biology: which would in any case leave her helpless as a pudding. Or a frog.

Something of herself, she was trying to tell me, had been given up in marriage, and would be lost further through childbirth. Of course there would be the blessing of a child – that first cry piercing the membrane of the world; and perhaps another, and another. And it would be exciting, true, but also rather alarming, to have produced a family; indeed, to have enlarged the world with several more human creatures; whereas I was as I was: plain and ill, yet whole, entire, un-pierced, un-reproduced. So that I thought to myself: the next time you are tempted to feel sorry for yourself, Alice: do not. You may be the last spinster on earth, but here you are. Now she was appealing to me: ‘‘You think men should be mastered, Alice?’’ I laughed. What did I know about men? But I owed it to her to be serious. ‘‘I think loyalty to oneself is the thing; husband, children, friends and country are as nothing to that.’’ I sounded, as ever, more sure of myself, more snappish, than I really was. And it shocked her, so I retreated.

‘‘Is it not sweet,’’ I asked, ‘‘having someone to comfort you in moments of distress?’’ I was thinking of the nights of course.

She laughed. ‘‘But Alice, as you must know, it is the other way round: it is our role as wives to comfort our husbands.’’

The other way round, I thought. Even so, I said, ‘‘Please remember it is only my book I press to my heart at night.’’

This annoyed her: ‘‘A book can be a great comfort, Alice, do not disparage its benefits.’’

‘‘No, I do not.’’ But still. I wanted to shake her, shout at her: You are married! How dare you be sour, you complacent little vole!? You are married! married! Instead I coo’d, ‘‘Your husband is delightful, everyone says so.’’ I felt a shiver go through her but she would not be drawn.

‘‘I’m sure he is,’’ she replied.

So much for your Boston enthusiasm. I tried to put myself into her shoes (which had pretty straps with covered buttons). I could hardly blame her for finding fault. Marriage, I knew, was not the perfect solution to happiness. But it was a refuge, a privileged club to which I was denied access; and therefore to me, precious. Which is why I could not forgive her for taking it so for granted.

She was all done up in her braids and collar and cuffs, and muff … which she suddenly flung off: ‘‘Let us do something naughty, Alice’’ – showing her pointy white teeth – ‘‘like we used to do as girls.’’ ‘‘What do you suggest?’’ I asked coolly. She put her finger in her mouth: ‘‘I have a longing to commit a sin.’’ ‘‘A sin …?’’ Now my curiosity was piqued. I was instructed to wait while she went down to the kitchen to consult Aunt Kate who in turn gave the order to our servant.

An hour later, a box was delivered from MacElroy’s in Harvard Square and brought up to my room. Sara held it on her lap as if it might contain something dangerous, explosives perhaps. ‘‘Go on, Sara,’’ I prompted, ‘‘or do you propose staring at it like a clairvoyant for the rest of the afternoon?’’ She gave a little shiver and, in time, began teasing open the lid, peering in, then sliding it closed again as if what she’d seen and sniffed at inside the dark box was just too impossible to reveal; then, again, raising the lid another crack, and another, until finally it was flung back and all was revealed. At which a low growl erupted from deep within her throat. And I thought: ah, so this is what happens when our miserable sex has an urge towards vice and wildness – why, we send out for eclairs! Which is what the box – which had come from our snooty Boston bakeshop – contained.

As we squeezed the pastries the cream squirted out the sides and down our wrists where it dripped off our elbows: the leakage was quite astonishing. Together we licked cream and chocolate from our fingers but it soon spread to our chins and cheeks as far as our ears. Later, the quilt and my night-dress had to be laundered and I bathed because the chocolate had somehow slithered between the buttons and onto my chest and stomach; and Sara’s muff had to be abandoned. There was even a smudge on the wallpaper like dried blood that had to be wiped immediately. And I was sick and regretted it. But I can still taste the sweetness, see our two faces lathered with cream-beards and chocolate moustaches grinning with pleasure like two five year-olds. And I do not blame her for her limitation of choice. Nor myself for mine.

Five

Katharine Loring Peabody peers round my bedroom door like a coy Dutch angel of the annunciation with her finger to her lips. Except that she’s neither coy nor an angel: ‘‘What, still in bed, Alice?’’

Katharine Loring was another ‘left on the shelf’ spinster like me, yet unlike me she was thoroughly transatlantic, stretchable and modern. And her perch had been self-chosen: a solid, safe place from which to step out into the world. She was no Sara Darwin, nee Sedgwick; she was nee nothing but that with which she was born. As she entered my room that day in early spring her name slipped between my lips, silky as a slice of ribbon. Katharine. I feasted on it until I was full: full of Katharine, and no need for eclairs. I breathed it out and the room was cleared of howling wolves and chattering birds and bats.

The facts. Katharine Loring Peabody: full of health and vitality; one year my junior. Fine features, elephantine ears. Eyes pale as blue smoke. Heroic bones yet of a willowy form, delicate as a tulip – bright and waxy to the eye and smelling of lemons with pointed petals arching like a royal collar or a pair of praying hands; with a long hollow stem which after some days in water ‘gives’, curving into balletic shapes. Oh, but she was no more a tulip than a slice of moon or melon. She was none other than my dear friend, my companion Katharine. Henry said he thought she combined ‘‘the wisdom of the serpent with the gentleness of the dove.’’ I told him I thought it had the makings of a good title for a novel.

‘‘Move over, Alice.’’ She sat beside me on the bed. ‘‘How are you?’’ she asked in her plain-speaking way. I said I was much improved and suddenly I was, though it may have been the effect of her rolling her thumb round the bone at my wrist as if polishing a pearl, and entreating me in her liquid voice to get better … to be better. After that she began pacing round the room talking of the ‘blanks’ in our lives. Which reminded me of my own situation.

‘‘In a hundred years from now,’’ I began – my voice was rather swoopy – ‘‘when the reader of that era opens one of Henry’s novels, they will come first upon a brief biography of its author in which they will be informed, following upon the basic facts of his birth, that his father was a prominent theologian, and his elder brother William was a famous philosopher. There will be no mention of a sister, however, or if there is, she will be described as a useless invalid.’’

‘‘Allowing it should be true,’’ granted Katharine, ‘‘your brothers have had advantages which you have not. We are living, as you know, in a man’s world. So you mu

st not blame yourself for not accomplishing what they have.’’

We’d been introduced at Ellen Tappan’s engagement party. ‘‘Alice, I’d like you to meet Katharine Loring’’. But no sooner had we stuck out our hands than we’d both been swept on to ‘widen our circle of acquaintances.’ I’d looked for her later on but she’d gone. After that I watched my brother’s friends drooping wetly over their intendeds, half-strangling them, and felt quite queasy. Love affairs were so much less appealing, I thought, in real life than in novels. And yet, as I moved about the party trying to avoid them I kept being drawn to them. Those flirting couples, the desire to be close, to absorb something of their heat; at the same time to get as far away as possible, to laugh at them, condemn them as absurd. And yet there was something deeply desirable about such a state of possibility, of things dark and hidden, even dangerous. William would soon know of it. Aunt Kate, who’d been married, though briefly and tragically, would certainly have known of it. Even Henry, who entertained pantings and spasms and convulsions in his stories, must surely have been touched by it. It was obvious of course what ‘it’ was all about: sex. There, I have said it.

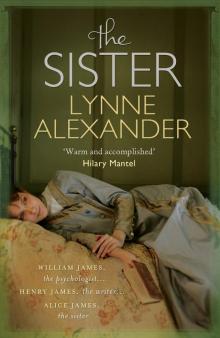

The Sister

The Sister