- Home

- Lynne Alexander

The Sister Page 2

The Sister Read online

Page 2

*

On the day of William and Alice’s wedding I lay in my bed where the wolves came to join me. By this time we’d become quite companionable. I had tried to get up to attend the ceremony but the wolves wouldn’t have it. Jealousy is a terrible thing. But really it wouldn’t have done to take a pair of howling wolves to a brother’s nuptial. My beasts turned circles and plopped down beside me, snuggling and snarling contentedly. I might have told William about them, and he might have been interested, but he was otherwise engaged.

Left alone in my bedroom I made a desk of my legs. My story would be called ‘The Wedding’. It began, ‘He had put her off with all his sweetly argued reasonableness.’’ It featured a man and two women; really it would be about a decision and its consequences. It began with the sound of church bells, the effect of distance on the bells’ pitch, how the air currents seemed to bend and twist them into a terrible out-of-tuneness, tumbling one tone upon another in a dreadful cacophany. I tried notating the sound – bronggonggggoinbbwrung – but decided the uncontrolled spray of letters on the page failed to conjure the actual blare of sound; and anyway, I concluded, best to leave such things to the reader’s imagination.

The bells could be ringing for only one reason. The man – I called him Billy – must have decided. The bride’s name is Anna Arbuckle. The rejected one is also called, coincidentally, Anna. They are distinguished as ‘One’ and ‘Two’.

Now what? I rested my pencil as I recalled the biblical Judith decking herself out to go and slay Holofernes, how she’d washed her body, anointed herself, plaited her hair, added bracelets and lilies and earlets and rings & etc. But Anna Two must get dressed and in a hurry if she’s to attend the wedding. What’s she to wear? Black, comes her reply: Let me wear black … It’s her voice, as if she were real and had the power of speech and a view on what she should wear to an imaginary wedding: Like the deepest of deep-water lakes: lapping, lazy, luxurious black. I shivered in my bed with a mixture of excitement and dread as Anna Two effected her transformation:

‘‘Anna Two (so I wrote) lights a candle and places it on her dressing table so that the flame illuminates her face from below, throwing dramatic shadows into the hollows beneath her cheeks, her eye sockets, her throat. Now she darkens her brows which are shaped like gannets’ wings. She rings her eyes in kohl, rouges her high cheekbones, outlines and paints her lips. Out of a secret box handed down by her grandmother she pulls yards of jet: necklaces, earrings, bracelets. This is no mere bedizenment. She is protected by her glittering black chains and ropes like plates of armor. ‘I am a walking blackness,’ she hisses. ‘I am gravity and I will drag them down with me. I am spite and venom.’ Her black dress is so dark it is almost invisible. ‘I am dressed in the night.’ ’’

Anna Two was now ready; but for what? I did not know. I was exhausted by my efforts, limp with despair on her behalf. Her power was an illusion. There she stood ‘all decked out’, magnificent arms akimbo but helpless, helpless. As was I. As for the story, it was transparently obvious. ‘That accurst autobiographic form,’ as Henry called it: ‘the loose, the improvised, the cheap and the easy.’ All my pathetic inadequacy flooded back in. Then one of the wolves came and curled up on the very page I was scribbling upon. So that was the end of that.

Sometime later Henry came to my room to tell me about the real wedding. I held out my hand to receive him, my head cradled by a bank of pillows. I imagined the scene as a painting, ‘Visit to an Invalid’ by one of those ‘impressionists’ Henry had told me about; perhaps the woman-artist called Mary Cassatt. We are enclosed in an envelope of light and air. Except that my bedroom is quite small and dark and stuffy with coaldust (an unseasonal fire smoldered in the grate) and my own fetid breath. Still to a certain eye the room and I with its busy patterns of quilt and wallpaper and carpets and curtains and invalid and visitor might have blended into one. The moment caught in pretty paint, only without the pain that kept me there.

June, the correct month for a wedding.

Henry began: ‘‘William nearly brought the whole thing down around our heads saying he could not go through with it after all, his vision had become blurred and he was having a nosebleed – he was sure he was suffering a cerebral hemorrhage. Once he was reassured to the contrary,’’ Henry continued, ‘‘he merely fussed and flapped about with rings and was his collar straight and who would say what at the breakfast; that occasion, when it transpired, was very sumptuous and agreeable and the whole affair pleasant.’’ He went on to describe the various dresses, one particular yellow satin with a yellow veil which he thought would have suited me. I disagreed, saying yellow, with my boardinghouse-pie complexion, was hardly my color – but he poo-pooh’d that. He described my friend Sara Darwin’s new husband as ‘a gentle, kindly, reasonable, liberal, bald-headed, dull-eyed British-featured, sandy-haired little insulaire.’ Which made me convulse with laughter in spite of the pain pinning me to my mattress.

‘‘And William’s Alice?’’ I asked. ‘‘She looked very pretty,’’ he replied simply. He would spare me the details, I saw, because once he’d ‘painted’ her for me in all her bridal finery, her true garments of gladness, I would never get the picture out of my head. It would be there forever:

Alice meet Alice.

But there was pain in Henry’s eyes too, though of a different kind from mine. Or perhaps not. It had taken William nearly two years to make up his mind – but he had finally done it.

‘‘He has divorced us,’’ I said: ‘‘He does not love us as much as he loves Alice.’’ Henry winced. I’d dared to say what he was feeling. Poor Henry. He’d been following William around like an orphaned gosling ever since I could remember but could never, ever, keep up.

As he was leaving he placed the bride’s bouquet on the shallow mound of my body. ‘‘For you, Alice, from Alice’’ – as if she’d thrown it and I had caught it. ‘‘How generous,’’ I muttered ungratefully, privately thinking: oh I will be next … But my furry companions disabused me of the notion. You are the last lorn spinster on earth. A-woooo, they concluded, raising their snouts to heaven. The gardenias soon began to turn brown and their rotting odor gave me a headache.

Two months later Henry sent me a story called Confidence in which a marriage separates two intimate friends. They do not remain separated forever, however, as the ‘groom’ ends up murdering his wife. Henry’s accompanying note read, ‘‘The violence of the denouement does not I think disqualify it.’’

Two

The next day I was visited by Clover Hooper – well her real name was Marian but everyone called her Clover. She had been to the wedding and had been distressed to find me absent. ‘‘Actually,’’ she confided, ‘‘I was rather intrigued. It occurred to me it might be a gesture of principle.’’

‘‘Principle?’’

‘‘Against marriage.’’

‘‘I see.’’ What I saw was that she had overestimated me; that she had taken me for a blue, an ‘intentional’ spinster opposed to spending her life as an appendage. An imposture of course; I was no Katharine Loring. I had failed to attend William’s wedding not because I was against marriage but because I was so much for it it made me ill to think it was not for me. As for saying But he was meant to marry me – that would have exposed me as cracked – childish. But Clover was perceptive, and knew me well, perhaps too well: ‘‘Of course you and William have always been very close,’’ she commented. ‘‘It must be hard to lose him,’’ she went on, ‘‘oh, and to another Alice.’’

‘‘Yes,’’ I agreed, relieved, as if the thoughts that had been going round in my head, of a world in which my name and everything else had been taken from me, was not merely the product of a sick imagination. On the other hand Clover had been, like me, one of the ‘odd’ ones. She’d studied languages; meant to travel; was clever. Henry had once called her ‘Voltaire in petticoats.’ But she had also spent time ‘inside’. ‘‘There, now,’’ she’d announced after her release from Some

rville Hospital: ‘‘I have done my duty. That was the smelliest and most hideous of all the bins.’’ ‘Doing her duty’ in a punishing asylum seemed to have salved her conscience, for aside from bandage-making and fund-raising – we’re talking War-time here – what were we to do? ‘‘We work so hard,’’ she’d complained, ‘‘but it is all for ourselves.’’

She took my hand; it was as cold as a corpse’s. Then she dropped it, ‘framing’ me as an artist would a portion of landscape.

‘‘May I take your picture, dear?’’

‘‘Clover,’’ I replied, ‘‘I am not a waterfall.’’

She scowled. ‘‘I know that perfectly well. I have little interest in the picturesque.’’

‘‘Go on then.’’

‘‘Good,’’ she said. Then she turned her back, distracted by one of her old photographs of The Bee hanging on the wall above the fireplace.

‘‘I see you aren’t there, Alice,’’ she observed, scanning it with her finger.

‘‘No, I must have been unwell that day. Katharine isn’t either.’’

She laughed. ‘‘Katharine was too academic for sewing.’’

‘‘Still is,’’ I said. ‘‘Nor are you,’’ I added, ‘‘in the picture.’’

‘‘That’s because I was behind the camera, silly. Anyway,’’ she added, ‘‘I was too skittish for quilting and such, I might have poked someone with my needle.’’

I said I thought it might have enlivened proceedings immeasurably, picturing some of our stodgier friends leaping about like stuck pigs.

But she’d begun rootling in her camera bag, reminded of her purpose. As she worked setting up her equipment I was reminded of the ‘old’ Clover. How she’d come to me one day with such excitement to tell me about her language studies; and then her plan. I’d always had a weakness for hearing of my friends’ plans, even if I couldn’t share in them. ‘‘Yes, Alice, to go abroad, visit … all sorts of places … with my camera of course …’’ she was almost twirling with excitement. And then in a conspiratorial whisper, ‘‘Even battle zones.’’ Battle zones? I had a sudden fear for her. If she was to carry out her plan, I’d thought, she would have to be more circumspect. I had advised her not to tell anyone. ‘‘Best not advertise it too loudly, dear. Make your preparations as you must; then, when you are ready, and only then, announce your departure.’’ She had regarded me with surprise. ‘‘You speak as one who has had such plans herself, Alice; have you?’’ But I would not, could not, say.

Clover, ten years later, was now quieter as well as sturdier, yet somehow smaller with it. ‘‘I’m sorry,’’ she said then. ‘‘For what?’’ I asked, but at that she became flustered and went about poking at things as if trying to set up a more tractable still life. Sorry; for what? For her good fortune and my less good? For all the weddings in the world not my own?

‘‘That you are ill, Alice,’’ is what she finally said.

But it was time to be ‘shot’. I doubted that I had the strength to pose, but she said I was to stay right where I was; she preferred her pictures ‘naturalistic’. She did however place an extra pillow behind my head. ‘‘We don’t want you looking half-dead,’’ she said. And then she ducked out of view beneath her black curtain as if sneaking a sniff or peering into a forbidden room, or even into some Williamish ‘beyond’. It seemed to me she was enacting her own disappearance even as she was ‘appearing’ me; yet no more so, I reminded myself, than Henry hiding behind his characters, and his words. Then came explosion after explosion.

Before she left she took my hands. Hers had warmed with her efforts while mine were chillier than ever. I tried to smile but found I was fatigued to the very muscles in my jaw: well, you would be too had you been ‘shot’ as many times as I had. Finally I dared to ask:

‘‘Did you photograph William and Alice?’’

She looked quite wolfish. ‘‘Absolutely not. Wedding pictures do not interest me.’’

‘‘Do they not?’’ I was pleased, I admit it. I could have petted her. Then I recalled one of our outings. Her sister Ellen had invited me to their place at Beverly Farms, and the three of us had gone for a walk along the coast – Ellen – Clover – me – and as the sun was setting Clover grabbed both our hands – she was between us – and made a solemn promise that she would never marry. But she’d lied of course. A year later she did. And to a Henry. She was now Clover Adams, nee Hooper.

I thought: Why, there are so many ‘nees’ in my life, I could open a horse stables. Not that I could blame her for that.

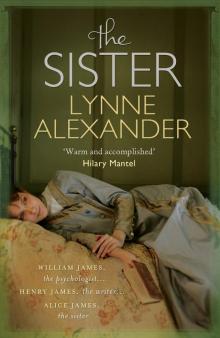

The resulting photograph had an eerie glow. It was shocking really: an old person in a young body, or do I mean a young person in an old body? Anyway, hardly what you would call lively or attractive. In it I appear to be saying something but with an anxious, almost querulous expression on my face. The light streams in from the window, lighting my forehead so it looks pale and sweaty. It also highlights, in an old masterish way, the folds and puffs of my sleeves as well as the neck-ribbon on my bed-jacket. But it is a ghastly, unaesthetic light. My nose and chin are too sharp, my forehead too high, my upswept hair too severe. I do not look well; but then I am not. I stare out from my sick-bed, fixed forever. It’s quite horrible, really.

*

Sometime later Clover’s sister Ellen came to see me, preceded by her exquisite Boston parfum. Here is a lady, I thought. ‘‘I see you are in a state, poor thing,’’ she informed me, ‘‘so I will not stay long.’’ She had brought a bunch of perfect roses, at odds with my own wilted state. But then, weirdly, she contratulated me on ‘the wedding’. ‘‘Why,’’ I pointed out, ‘‘William and Alice did not marry me, merely one another.’’ She registered alarm in the manner of very superior Arabian horse. I thought to put her out of her misery by asking instead about her own marriage.

‘‘Oh, Whitman, Whitman,’’ she fairly coo’d: the breathy whistle of a bird calling to its mate. ‘‘Why, the things people tell you when you’re married, Alice, you would not credit it.’’ She went on, ‘‘Some even intimate that the matrimonial state is rather a complicated one and subject to more or less rubs of one sort or another.’’ She drew herself up. ‘‘Can you conceive of such a thing?’’ And then she burst out, ‘‘I can’t, I’m sure!’’

Well, there was not much I could say to that, though I thought What gush. But then my father came to mind, that soft-headed old turnip who believed in goodness and marriage, so I told myself to be pleased for her, to allow her pleasure to ‘spill over’ – if such a thing were possible – into my lap too. Yet her certainty, her denial of any ‘rubs’ struck me as rather brittle, not to mention unrealistic.

‘‘I’m pleased,’’ I responded, ‘‘you’re finding wedded bliss with your beloved Whitman. But,’’ I cautioned, ‘‘it would be well not to take yours as a sample of marriage generally, especially as you have only been married under a year.’’

‘‘Oh, Alice!’’ she cried, ‘‘don’t be such a killjoy, your own time will come and then you will find out for yourself how absolutely divine …’’.

But my time I suspected would not come and I would not find out for myself. After she left I fell into a deep sleep. In my dream there were two sisters named Ellen and Clover. They could not be more different, yet I woke fearing for them both.

Three

I had a chamber pot: a shapely, ladylike thing resembling a giant cup with a fluted handle. In the dark I felt my way round its embossed rim as if reading phrenological bumps on a skull. I could not in the dark make out its sprigs of blue roses though I knew exactly where they were; and that there were thorns painted with the flick of a single-haired brush along the stem. The pot’s roundness felt comforting: like a globe, like the earth. A joke of course. It was nothing but a hollow receptacle absurdly decorated and inconsistent with its true purpose: to fill with my body’s wastes. That splashing sound in the night. When it was full I would slide it back under my bed, stuff my nightgown between my legs and curl into a tight hard ball.

I guess I lived in my bed with the chamber pot lurking coyly in its commode for the next year and more. My ‘monthlies’, even less ladylike to mention, came like rivers in spate and clotted with gore. I counted sixteen in one year. But the wolves were happy: they lapped greedily while I held my cramping belly with one hand and buried the other in their thick matted fur.

My nurse Milly rolled me from side to side like a sausage. There were bowls of warm water and boiled rags. After I and my bed-linen were made clean again my father would come clunking in to read to me from one of his theological tomes, but I failed to distinguish his words from the chattering birds who’d returned during the night disguised as bats spangling the ceiling with their wings and staring down at me with their red glass-bead eyes. They adored blood of course.

I had my share of visitors. Well, visiting is what one did: young and not-so-young ladies hoping to exchange toothsome gossip. However they came bearing offerings as to an effigy, smiling pityingly/encouragingly &etc, while I lay with my arms stuck outside the quilt and a planted expression upon my face. In some of their smiles I divined a barely suppressed impatience Oh, do get up. … But mostly they accepted my horizontality. They had no choice of course. As for me, my body ruled: Movement comes to stillness, it once instructed, ludically – which I was able to interpret as: Visitors may come and go; I must be still as a pudding. At some point William accused me of ruling over the family like the sun in the heavens. Wildly inaccurate of course. I was merely a pathetic, sick spinster. ‘‘But what do you do?’’ Fanny and Annie and Sarah would ask, and I would say, ‘‘I do not do, I simply am. I exist in the way of a mushroom.’’ And they would look me up and down trying to decide whether or not I was poisonous.

The Sister

The Sister