- Home

- Lynne Alexander

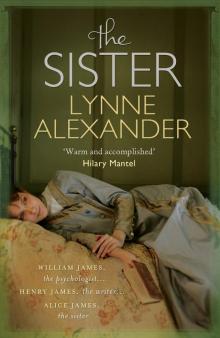

The Sister Page 25

The Sister Read online

Page 25

But she stands her ground. ‘‘Henry will make the James name famous for all of us,’’ she declares.

William is looking fierce, embattled, left out.

Alice hisses, ‘‘Unscrew your eyes, Willy, or they will stick like that!’’ But he ignores her; he is far too cross.

‘‘And how,’’ he asks, ‘‘does that compare with Wilkie and Bob giving their lives for our country?’’

‘‘But they have not,’’ asserts Kitty: ‘‘Unless my eyes deceive me, they are both, thank heavens – even Wilkie with his wound – very much alive.’’

‘‘And long may they continue,’’ puts in Aunt Kate.

‘‘Amen,’’ adds Mother. ‘‘Would anyone like more pudding? cake?’’

No one answers her.

‘‘Anyway, Willy,’’ Alice pursues, ‘‘you haven’t either – given your life.’’

‘‘Alice!’’ booms her Father. He has led them all to believe that William and Henry were meant for higher things than War (like Writing and Science).

‘‘Please, dear,’’ pleads Mother.

‘‘But it’s true,’’ cries Alice.

William holds up his hand and smiles an odd sort of smile. ‘‘She is quite right, the little hyena.’’

Alice’s lip trembles.

Mother turns to her: ‘‘Well, if you will sass your brothers!’’

William goes on: ‘‘Our younger brothers are the best abolitionists you ever saw, and make common ones feel very small and shabby indeed. Unfit for a life of action as we are, I believe we are two of the very lightest of featherweights.’’

Alice observing Henry notes how his lips, top and bottom, roll inwards until they nearly disappear. No,William, I do not feel light as a feather, or in the least small and shabby. But is he pretending? she wonders. However clever, he can never ‘keep up with’ William when it comes to ‘manly’ things; and he must know that Wilkie’s ‘wound’ is ever so much more romantic than his own ‘obscure hurt’. As for Rob leading black battalions into war – the thought of actually doing such a thing makes him feel quite peculiar, though he would like to have the experience of it. Oh, yes, she decides, that is what he envies.

But Father is furious. It does not matter what each is doing: brother should not turn against brother. It is a sin. And a sister should not take sides.

‘‘My d-d-dear boy,’’ he instructs William, ‘‘you must conquer this curse of self-doubt.’’

Cousin Kitty folds and unfolds her napkin.

‘‘Don’t be frightened,’’ says Mother, ‘‘they won’t stab each other. This is usual when the boys come home.’’

*

Next morning Alice and cousin Kitty go for a cliff walk under a low, grey Newport sky. ‘‘And what are we to be thankful for?’’ asks Kitty. Alice stops, shocked. ‘‘You have only recently been married, surely you must be thankful for that?’’ ‘‘It has been two years now,’’ rejoins Kitty, as if that must make a difference. ‘‘But is it not wonderful,’’ entreats Alice, ‘‘to be married – and to a physician?’’ She imagines being tended by an all-powerful being. Kitty smiles ruefully, ‘‘Some day, little Alice, you will find out.’’

Returning to the house, Alice goes up to the attic which Father has had built on so that they can gaze across the lawns to the sea; though mostly the great Austrian pine blocks their view. She tries to give thanks but all she can think of is Henry’s hurt and William’s poor eyes and stomach and feelings of shabbiness, and Wilkie’s war wound that makes his ankle throb in the night, and the sore place on his back where shrapnel has lodged and that she has been allowed to touch; and Father’s peg-leg, and Aunt Kate’s ‘frightful’ mistake, and now poor cousin Kitty with her nerves and having to have ‘rests’ in insane asylums. Not to mention her marriage which has not saved her from anything and has itself become a hurt.

Alice, gazing out of the attic window, spies her two older brothers circling the garden below. As quietly as she can, she raises the sash, in time to hear Henry say he wished sooner to descend to a dishonoured grave than write the sort of book William has expressed admiration for. She does not hear William’s reply. She wishes she had not heard any of it.

One by one the brothers ‘peel off’: Wilkie and Bob to their barracks; William to Harvard; Henry also to Cambridge (but they do not travel together), and Cousin Kitty back to her husband and to volunteer, along with her friend Miss Alcott, for nursing duty. Only Alice is left behind to roll bandages and assemble bullets. Alice, reading stories in Lady Godey’s Book about wounded soldiers falling in love with their nurses, judges herself the most idle and useless, the most peripheral and irrelevant of them all.

Wardy was quite right about not having a family to make it a convincing Thanksgiving, especially as she and the Smiths had both found excuses not to join me. So there I sat alone at Henry’s vast table gazing out across de Vere Gardens with its mostly bare trees and wrought-iron spikes. The sun was about to go down behind the pines. A band of cloud had formed but the sun shone through it lighting up the handsome rosewood dining table. Bandages and bullets … I recalled the feel of the bandages as I rolled them into bouncy bundles and lined them up, just so, neat as socks in a drawer, but quite useless really except for staunching blood and hiding the wounds made by the bullets which had made the bandages necessary in the first place; and now how absurdly cruel they both seemed, the hard and the soft, that Wilkie was dead (along with so many others, white and black), and Rob – well, had he ever recovered? The candied sweets had turned out far too sweet, the sprouts were overcooked and the turkey rather dry. We’d had little appetite, in any case.

‘‘Will that be all, Miss?’’

‘‘Yes, thank you, Smith.’’

Beside my plate were notes from Aunt Kate, cousin Kitty, William and Henry, all wishing me a Happy Thanksgiving. Nothing from Katharine. I remained sitting staring out until the last light faded and the window dissolved into a huge dark shape floating in space. William and Henry, I thought, had anything changed between them? William had come to understand that Henry had little respect for his literary pronouncements, and Henry knew absolutely and conclusively that William had no love for his novels. Yet somehow it did not matter, or not much, I thought – a kind of comfort – so long as Henry acknowledged an innate superiority in William, and William was allowed to patronize his younger sibling. For they were brothers after all; and their small war was, if not winnable, at least containable. They would both survive it.

Smith threatened to light the lamps and candles but I refused, continuing to sit with my hands out before me like one of William’s batty seance-attenders waiting for the table to speak. And then – so I imagined – it did. It told me I must do something with myself, for myself.

But what?

Gradually a plan took hold: I would leave de Vere Gardens and London. I would go to Leamington Spa where it wasn’t so queer to be ill, and where I would be independent of Henry. I would book myself into The Regent – no, too self-important – The Temperance: yes, that would do while seeking a more permanent accommodation. But I would need help. I rang for Smith: ‘‘Where is Wardy?’’ I asked. ‘‘Hiding,’’ came the reply accompanied by a rude snigger. Poor Wardy, I thought: she feels pushed aside by The Smiths. But that will stop now. ‘‘Please tell her I need her.’’

Thirty-nine

Wardy, chuffed to have been summoned and tickled to be going to live in the fashionably ‘Royal’ town of Leamington, was galvanized into action. Chuffed and tickled and galvanized: such words.

‘‘That’s right, Wardy, just like the Queen.’’

‘‘Do not mock me, Miss,’’ she warned fitting fists to hips like a threatening pitcher before snatching up a photograph of me taken in ‘73 with my hair up in braids, my whole life before me.

‘‘Is that really you?’’ she asked.

(Was it my turn to be mocked?)

‘‘Yes,’’ I told her, ‘‘and it will need wrapping in newsp

aper.’’

‘‘Huph,’’ said she, which I translated: as if I didn’t know.

We had returned to Bolton Row where we were surrounded by packing boxes and trunks. I’d written to Katharine just after Thanksgiving telling her we were moving, and had received a letter promising to ‘take you in charge for the move’. But the move was upon us and she was not. At some point a rain-blurred postcard had arrived repeating the promise.

Wardy, meanwhile, had persuaded me to ‘go through’ my possessions. Go through? ‘‘If this is your artless way of trying to distract me,’’ I warned her, ‘‘it will not work.’’ But I was quite wrong, it did work. I became so caught up I was able to ignore the nerve pain that nipped me here, there and everywhere like some crazed crab.

I sat, or rather reclined, while Wardy held up various garments for me to decide yea or nay: ‘visiting’ dresses, feathers and furs, hats and shoes, belts and other miscellaneous accessories. A ‘thumbs up’ went only to practical, comfortable, warm (Wardy: ‘spinsterish’) items; anything else she could take away for herself or her Aunt Flo, or cut down to give to her hospital children.

‘‘No, too tight … too constricting … quite ridiculous … too young: I will never be seen in such a thing again.’’. Only the brown velvet dress could stay, and the green serge jacket with the velvet collar and plain black skirt.’’

‘‘And the crinoline?’’ It stood by itself like a bird-less cage.

I would not be its catch: ‘‘Away with it.’’

‘‘But surely,’’ she pointed out, ‘‘you will be needing it to go out in, even for a stroll around the Pump Room or Jephson Gardens.’’ She had memorized Leamington’s main attractions.

‘‘I won’t mind in the least,’’ I reassured her. ‘‘I shan’t be going out much, if at all, and if I do I’ll droop my bedraggled, un-crinolined way about town.’’

She objected to my ‘plainness’: why if I could afford it?

Because, I replied, I objected to flounces and gewgaws.

‘‘Huph,’’ came again as she bent to retrieve a fur muff from the bottom of the trunk, dangled between her two fingers. I waved it away: ‘‘I will not be requiring the services of a skinned muskrat.’’ She plunged back in: ‘‘Now what do you say to that, Miss?’’ she asked admiringly, flicking the fur bobbles as if they were bells. And there I was again, fourteen years old, in Paris, wearing my new white fur tippet. The family is on its way to the Louvre where I am about to witness the great paintings, and all the people gazing at them. Henry is to my left, William to my right; the smaller boys trail behind along with Father and Mother, arm in arm. I am so well, and therefore so rapturously happy, that every so often I rise up in a skip to make the bobbles tying the tippet bounce and hit me in the nose, to remind me that I am not dreaming it.

‘‘Give it here,’’ I ordered, wondering half to myself if it was possible that I’d ever worn such a thing.

‘‘I’m sure I do not know, Miss,’’ replied Wardy. ‘‘I expect you were young and foolish once.’’

‘‘And now, you mean to say, I am merely old and foolish?’’

‘‘I did not say that, Miss; you are always putting words into my mouth.’’ Words, I thought: perhaps I should cast those off too?

‘‘Am I, Wardy?’’ I asked, serious now.

‘‘Are you what, Miss?’’

‘‘Nothing, then, never mind.’’

We continued in silence, sifting through another box containing pictures and gadgets that I’d carted all the way from Boston. The photographs of my parents and brothers, oh, those must stay; but ice skates? hiking boots (worn traipsing after Katharine in the Adirondacks)? No, I would not be hiking or skating again. I had a vision of my discarded books and boots and muffs tumbling through the air like strange acrobatic birds.

‘‘What catches you, Miss?’’

‘‘Nothing,’’ I said, suddenly faced with the truth of it. Like shedding one’s old skin after sunburn. Oh, one was tender and pink and raw but, if anything, more alive for the honesty of it. Nor would it end there. The ‘stripping down’ had only just begun. In Leamington it would go on: from skin to flesh to bone to …

‘‘Wardy! I have just remembered something.’’

‘‘Yes, Miss?’’

‘‘There’s a lot more stuff that I left in the Boston storerooms.’’

‘‘What will you do with it? Do you wish it sent over?’’

I shook my head, ordered her to bring me pen and paper upon which I scrawled:

Dearest William,

I have just remembered the stored things – a fair old mix – mostly junk but a few good pieces. If there is anything you can use do help yourself …

I recalled a red rug which would do, I thought, for his study, and another rug for their parlour; the old kitchen traps would be useful in the country; and there were beds, blankets and linens. The keys to the trunks, I instructed, were with my lawyer. The pictures would do nicely on their walls. That left the crockery … barrels of the stuff. For some reason those felt harder to let go of. I saw myself setting my mother’s favorite pieces out on a clean cloth for the boys and their wives and children, the gold rims repeating one another, the chink of cup against saucer … A fantasy of course. Still, I added a ‘P.S.’ saying perhaps the crockery could be kept aside for me. And the oak rocker with the carved back and upholstered seat? Oh, that, that I would like sent if he would be good enough to ship it across. The rocker would remind me of the sea, and my cottage at Manchester.

Weary now, I signed the letter and closed my eyes. Opened them. Before me, a familiar figure leaning in the doorway. An apparition, I suspected blinking hard.

‘‘Gracious me,’’ gasped Wardy, holding her heart.

‘‘So, Queen Alice reigns from her bed,’’ said the apparition.

I stared, rubbed my eyes. It was all too melodramatic, too absurd; like a scene out of Goldilocks and the Three Bears, and me about to yelp: And there she is! For there she was. Or perhaps I’d conjured her too. But no: ‘‘What’s all the fuss, Alice? I told you I would get here in time to help you move.’’ I opened and closed my mouth fishlike.

‘‘Aren’t you going to say anything?’’ she asked.

‘‘You look well ventilated,’’ was all I could think of.

She and Wardy set to work. In between each completed packing case Katharine would return to lay her hands on my shoulders and tell me of another adventure – she’d been hiking in the Adirondacks – or another success with her students; or cover my eyes with her open palms from behind as children do; or cradle my head loosening it from its fixed tilt; and then back to piling more books into a packing case.

That evening it began to rain. ‘‘The gutter must be blocked,’’ she diagnosed, going to the window and looking up towards the roof. The blockage caused the rain to fall in drumbeats, in clots and clumps until we were enclosed in an almost solid curtain of rain separating us from the outside world. But meanwhile there we sat, warm and dry, enjoying the last fire in that place, with me reading from Henry’s chilling tale ‘De Grey’, and Katharine interrupting with more stories about camping in wild weather and tramping vast distances and coming upon meadows filled with late wild flowers and, once, meeting a bear which she claimed to have chased away by bellowing boo at it.

The next day we boarded a train heading North. Wardy, no doubt feeling displaced, had decided to visit her Aunt for Christmas; she would return in the new year. I gave her her Christmas present (the fur tippet I’d managed to squirrel away, which pleased her inordinately), and bid her a happy holiday. So we risked travelling on our own; after all, I now had Katharine beside me, Katharine who was real and had turned up as promised, albeit rather late.

We were just pulling out of the station. Katharine threw off her hat and raised her arms to place it upon the high rack, swaying with the movement of the train yet keeping her balance. She moved so loosely while I sat like a toadstool, or a toad. Then she flopped b

ack down and there were her ears which were quite enormous in relation to the size of her head. Really, I thought, she should comb her hair over them instead of behind. But what did my Katharine care for vanity?

‘‘What are you staring at?’’ she asked over her spectacles.

‘‘Nothing,’’ I lied, reaching over to tuck a wayward strand behind one of said ears. At some point I tilted my head so it rested against the glass. ‘‘We can’t have that,’’ Katharine pronounced, ‘‘you’ll wake with a headache and a jarred spine.’’ Her arm went round me. If the other couple in the carriage thought it odd, they did not show it. In any case, what would they see? A tall thin woman, rather severe, considered by some to be ‘masculine’, with her arm around the smaller woman who appeared more fragile, perhaps ill. Whatever it was they were seeing, or told themselves they were seeing, let them see it, I thought. We would keep hold. A new year was upon us, and my Katharine was back, and we were on our way to Leamington.

IV. LEAMINGTON SPA

(1887–1889)

Forty

We’d crossed Newbold Terrace and were entering the underpass, dark and slippery with mud, its brick walls running with slime, when a shadowy shape loomed up ahead of us. ‘‘Do watch where you’re going, dear,’’ I warned. Katharine charged straight on. ‘‘Look out!’’ I yelped. The kissing couple – for that is what it was – leapt aside, flattening themselves up against the wall as we sailed past and out, straight through a pile of dog mess. ‘‘Damn,’’ I cursed under my breath, ‘‘now Wardy will have to clean the wheels.’’ Katharine threw up her hands, ‘‘Oh, don’t take on so, Alice.’’ We were like an old married couple sniping at one another to slow down … speed up … wrong way. . . . And what of the kissing couple? Had she intended to bash into them, thus forcing them apart? Or had she simply not seen them? The simple explanation was she was still sore about the move and behaving recklessly.

The Sister

The Sister