- Home

- Lynne Alexander

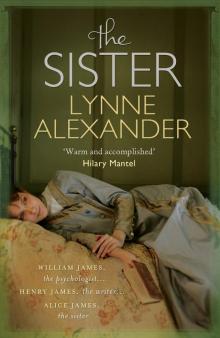

The Sister Page 20

The Sister Read online

Page 20

‘‘Your brother to see you, Miss James.’’

Henry hesitated, as if fearing a clawed-and-fanged Katharine might spring out at him from the skirting boards to attack him for daring to use his influence on her behalf.

I paused in my letter-writing: ‘‘It’s alright,’’ I said, ‘‘she knows you were trying to help.’’

‘‘Lord Rosebery: ah, that … ought I to apologize?’’

‘‘I suppose you might if you ever meet face to face. Your avoidance of one another is becoming farcical, like something your friend Wilde might dramatize for the stage.’’

‘‘I will mention it to him when next I see him. But speaking of writing, I’m interrupting your flow: shall I wait?’’

‘‘It’s only a letter to the Prime Minister.’’

‘‘Ah, and upon what grave issue are you lecturing him?’’

‘‘Don’t mock, Henry. They voted to repeal the Contagious Diseases Act. An abomination, as I’m sure you realize.’’

He felt for his beard as a child for its cuddly toy. My brother, I thought, does not like laws or history ‘in the raw’; to keep his attention I must make a scene of it. But how? The law as it stood blamed women for prostitution while their male clients were let off without a blemish to their record. Yet prostitutes, as Miss Butler had pointed out, were clearly victims of male lust.

‘‘Henry,’’ I tried, ‘‘I would be on the streets if not for …’’

‘‘Alice?’’

‘‘Henry. Please pay attention. Had I been born into poverty, had I not been the beneficiary, like you, of a protected, privileged upbringing, I might well have been forced into that awful gulf from which society has done its best to make escape hopeless.’’

‘‘Is that what you have written to Mr Gladstone, Alice?’’

I admitted I had written something along those lines. ‘‘I have also pointed out,’’ I added, ‘‘what I and many others perceive to be the State’s true concern: By arresting soliciting women – even tho’ it is not illegal – and imprisoning them, it ensures that men can hire prostitutes without infection. Can that be fair, Henry?’’

‘‘Fair …?’’ His hair, which had been receding at an alarming rate, had been cut close to his scalp, producing the effect of a rather dirty egg. ‘‘My dear sister, it is not a word I hear much spoken nowadays.’’

‘‘But surely you believe in upholding it?’’

Henry stood before the peacock screen. I suppose he was thinking of one of his characters and whether or not they would concern themselves with the nature of ‘fairness’.

‘‘Tell me about the demonstrations,’’ he said.

‘‘You should ask Katharine. She was there: as you well know.’’

He nodded. ‘‘But you supported their cause?’’

‘‘Naturally.’’

‘‘Indeed,’’ he pursued, roused by the ‘scent’ of action: ‘‘I believe, were you not ill, Alice, you might have enjoyed a career as a dangerous little revolutionary.’’

‘‘In that case,’’ I asked, ‘‘do you suggest, like Wardy, that it is just as well I am ill?’’

Henry sat, folding his hands humbly into his lap: ‘‘We are well out of it, are we not, Alice?’’

‘‘Are we?’’ I challenged, unsure of what it was we were well out of (marriage? liaisons? political action? employment?).

Silence.

My ‘success’ was making me reckless. I went on: ‘‘What, Henry, would you say about a tale that alluded to certain violent movements – socialism, anarchism, ‘terrorism’- responses to the general malheur one is aware of in this strange country in which we find ourselves marooned?’’

Henry unfolded himself.

I related my idea. The tale would be set in London in the year following Krakatoa. I ‘painted’ the opening scene as I imagined it, describing how every morning and night for two years after that event these London skies – thousands of miles away from the original blast – were still affected, turning blood-red followed by stainings, layered washes and glazes of carmine, cerise, orange and purple, one sliding into the other. I went on to explain my idea, how it was the explosion which had caught the attention of a certain character; the explosion as a symbol of what was needed to address the malheur of her society.

Henry ran an unlit cigar along his upper lip, taking in its aged tobacco scent.

‘‘Go on,’’ he encouraged. But suddenly, doubting my own capacity, I could not. I was no Henry: Henry who could, with a mere glimpse from a doorway or a window, suggest an atmosphere of tension, a premonition of imminent disruption. Henry, having strolled the wet streets of London, could describe the reflections of the lamps on the wet pavements, the way the winter fog blurred and suffused the whole place producing halos and radiations, trickles and evaporations, on the plates of glass. Henry could make them shine like pomegranite seeds; make you want to slurp them up so that the blood-red juice ran down your chin in the most unladylike fashion.

‘‘Alice …?’’

‘‘Yes, Henry,’’ I managed to reply. I was thinking, unfilially, how ‘my’ tale – if it was mine – would have little or no style, and therefore less ‘rigmarole’ (as William rudely called it) than Henry’s; on the other hand, it would have more ‘feeling,’ as Aunt Kate required; added to that, its very own explosive quality. My Krakatoa would crackle and hiss and spit; my Krakatoa would rain down its sinister fallout over London; my Krakatoa would explode, again and again …

‘‘But what,’’ he was now demanding, ‘‘does your ‘heroine’ do; what is her raison d’etre?’’

I hesitated. I had begun to regret having spoken; but it was too late for a retreat.

‘‘Oh,’’ I began, feverishly nonchalant – I’d burst into a sweat – ‘‘she is a rich, strong, vital American … During one of her tramps around London she becomes aware of herself as a hypocritical ‘adventurer’, a foreigner enjoying the freedom and ease of London thanks to her money and position. But she begins to wonder, feel, what it would be like if every door of approach -into the light, the warmth and cheer, into good and charming relations – were to be slammed in her face.’’

‘‘Ah,’’ supplied Henry, ‘‘a revelation.’’

‘‘Are you laughing at me, Henry?’’

He denied it; once again, in spite of my obviously deteriorating condition, urging me on.

‘‘Leonora …’’ – there, I’d named her – ‘‘… is in a state of exclusion, of weakness, having chosen to live in mean conditions among the lower manners and types, the general sordid struggle, bearing the burden of her prostituting position with its ignorance, misery, poverty, vice …’’ I broke off, for without first-hand knowledge of low-life London, of what precisely it would mean to sell one’s body, not just once but repeatedly (numbingly, painfully), how could I, or for that matter Henry, describe such a thing?

‘‘But why has she come to Europe?’’ Henry was needing to know: ‘‘what has brought her here?’’

I explained how she’d been transplanted from America and promised marriage, then abandoned for some unaccountable reason.

‘‘Yet she stays on?’’ he guessed.

I nodded. ‘‘She observes the seedy goings-on beneath the vast smug surface of the City.’’

‘‘She prowls about,’’ interjected Henry gazing intensely at the blank stretch of wall opposite as if he can see the bleak scene forming there: ‘‘turning her gaze on the vast, tragic, dark, menacing City …’’

I was beginning to feel weak. Still, I managed to stress, it was her experience of the ‘low’ life, a life at the hands of men who would handle her roughly, that would radicalize her still further.

Henry leant forward. Such a character would only be of interest, he supplied, if she had the advantage, or disadvantage as the case may be, of an acute, indeed, a hungry sensibility. She would note as many things and vibrate to as many occasions as I might venture to make her. ‘‘Thus,’’ he conclud

ed, ‘‘it is necessary to give one’s own fine feelings to the humbled young woman.’’

‘‘Humbled, Henry?’’ I cried, sick with outrage, yet hobbled. I saw that I’d already lost my Leonora to Henry. But I must insist on my part in her reality, her truthfulness: ‘‘On the contrary,’’ I managed. ‘‘Fine feelings she may have, but that alone would become tiresome; no, there is the question of what she will do: dream, risk, attempt …’’

‘‘Ah,’’ he pursued excitedly, ‘‘an adventure!’’

‘‘No!’’ I shouted. I had never raised my voice to him before – but there it was. ‘‘Henry,’’ I kept on, ‘‘how infuriating you are! An adventure indeed: you pompous, patronizing … pig!’’

He rose, alarmed. ‘‘Alice …’’ Clearly he feared another ‘attack’. But he could not stop me. Leonora’s resolve, I told him, would harden. She would give away her money. She would rent a house in the poorest section of London. She would make contact with … the agents of change. She would do more than merely fume, like the others, against injustice … She would show all the flaneurs, the players, that this was no mere adventure … She would sacrifice her life for this. ‘We’re looking for a new order,’ Leonora would rail, fuming, ‘and what do they do but stopper our mouths with, with … cheese.’

‘‘Her clarion call,’’ I added, ‘‘is: ‘I am Krakatoa: see if I am not’!’’

I felt the air crackle about us.

‘‘Do you believe in her, in it, Henry?’’ I whispered. It no longer mattered to me whose tale it was, only that it should ‘live’.

My brother stood once again before the peacock screen. Had I been an artist, I thought, that is where I would paint him, a black shape against the brilliant, stylish screen. ‘‘I believe,’’ he replied nodding in its direction, ‘‘only in keeping out the draft.’’ And with that he reclaimed his seat, hooking the thumb of one hand over the pocket of his vest, and the forefinger of the other through the fine, ear-shaped handle of his tea-cup. It only just fit. I wondered what William would have to say about ‘keeping out the draft’. Did it express a need for keeping out certain unpleasantnesses? But I was the sister and sisters, being creatures lacking mental ‘stoppers’, are free to say anything. And, peacock screen or no, there was still a draft howling about our feet.

Henry’s eyes, I saw, had hooded over again. He would take his leave. But not before I’d thanked him for the Rigatello he’d brought me from Venice and given Mrs Dickson, (who’d forgotten to give it to me until that morning).

‘‘Thank you, Henry, I adore strong Italian cheeses.’’

*

After that – but what had happened?- had I erupted? – I was allowed no visitors. It was for my own benefit, as Katharine explained, acting as my protector-cum-jailor while writing up the results of her work: a comparative essay entitled, Home Studies Programs for Disadvantaged Women in England and America.

A knock at the door which I know to be my brother’s. Mrs. Dickson gets there first. She smiles and ushers Henry in as usual, at which point Katharine, who has flown down the stairs, bars his way. ‘‘Alice isn’t well at all – she cannot – will not – see you!’’ I hear. The exclamatory rise of her voice carries. It’s a lie, of course; I am never too ill to see Henry. But I haven’t the strength to run down and deny it.

What will Henry do?

Silence. My brother is, as he was when we were children, when I depended on him to defend me against William (Leave her alone, I imagined him telling William, quietly assertive, manly, while removing me gently from the fray) overwhelmed, reduced in the face of a superior force. Now, once again, he stands at the bottom of the stairs as if magnetized or watching a play at the theater.

The next day morning there is a peremptory knock – not Henry’s. Henry has sent one of his doctors to call on me.

‘‘Shall I let him in?’’ asks Katharine.

I nod.

‘‘Shall I stay?’’ she asks.

I tell her I would rather face the butcher alone this time, if she doesn’t mind.

‘‘As you wish, Alice.’’

Dr Hooper is an energetic man with faded red hair. The contrast is most striking: I feel certain that if I poke one of his cheeks the flesh will bounce back with youthful vitality; while the hair can only announce itself as a senescent thatch. He produces a hand for me to shake. I extend mine but somehow it misses its target.

‘‘Ah,’’ he says, revealing a slug-like tongue upon his palate. Then, bizarrely: ‘‘Has the protuberance of your eyeballs increased lately?’’

‘‘Not that I am aware,’’ I reply.

After an examination of my heart another portentous ‘ah’, so that I fear a diagnosis of heart-failure at the very least. But no, it is a ‘vivacious’ organ. He begins packing up his instruments then stops and straightens:

‘‘I am inclined to tell you the truth, Miss James.’’

At least this one doesn’t presume to call me Alice. ‘‘I expect nothing less.’’

‘‘Do you wish to hear it?’’

‘‘I do.’’

Katharine, when I later report it to her, says in her thoughtful way, ‘‘Is the man, I wonder, a maniac, or a genius?’’

Wardy, on the other hand, when told of the doctor’s ‘gruesome’ prediction, cries out: ‘‘Mercy! He never! How could he say such a vile thing – and then leave you his bill?’’ When I laugh, she slaps her skirts, ‘‘You shock me, Miss. I will never understand you, that is a fact. How you could be cheered up by such is beyond me, truly it is!’’

You will not die but you will suffer to the end.

Thirty-two

‘‘Miss Woolson,’’ announced Wardy – and there she was, Henry’s ‘friend’ Constance Fenimore Woolson.

She is plain, small, inclined to embonpoint.

She is overdressed.

She is delicate of health.

She is ages older than Henry (well, three years).

She is a she-novelist.

She is deaf.

She is a ‘meticuleuse old maid’ (Henry).

She is …

What is she doing here?

Henry, having spent the winter months with Consance on the Continent, had deposited her back in Italy like a small but dangerous parcel before returning to England himself. Yet here she was again. Earlier I had received a letter saying she would be coming to Oxford ‘to do research’.

She has come to sniff out Henry.

Constance – I could not bring myself to call her Fenimore – produced from her voluminous holdall an ear trumpet. It was not the usual ‘horn’ but a new-fangled telephonic device with a mouthpiece at one end, an ear-piece at the other, and connecting the two, a six-foot wire. ‘‘It is only old friends who will take the trouble to speak into it,’’ she proclaimed, tossing the ‘telephonic’ end over to me. It slid to the floor like an eel. Constance, tutting, returned it to my lap. ‘‘There now,’’ as if to a child: ’’try – and – keep – hold – of – it.’’ I managed to do so. ‘‘Just speak naturally, not too loudly or you will blast my brains; and not too softly or I sha’n’t hear a word. Now say something,’’ she ordered. I uttered the first word that came into my head: Henry. ‘‘Too soft,’’ she bellowed from the other end: ‘‘louder please’’. ‘‘Drawers,’’ I boomed, which made her blink. ‘‘There is no need to be vulgar, Alice, as well as over-loud.’’ We went on like that until we reached an agreeable compromise.

She settled herself in the square old oak, her elbows propped onto its high arms. I thought of a bull I’d once seen, huge and dignified and full of its own bullish gravitas but with a pile of straw sitting like a church lady’s hat perched between its horns. The effect here – her torso was quite majestic but her feet failed to touch the ground – was similar. Yet one tittered at her (likewise the noble bull) at one’s peril, for she was a woman of depth, insight, sensitivity, not to mention considerable writerly talent.

‘‘How are you, Alice?’�

� she asked in her throaty way. Indeed, so encouraging to intimacy was that carefully-modulated voice, I was tempted to confide the doctor’s hopeless diagnosis. But I caught myself up: death one could converse about, but not eternal suffering. At last I said, with some truth:

‘‘I have been enjoying a period of relative good health and revelling in it. The doctors round about say I will either die or recover – which they have been saying ever since I was l9 years of age. And, as far as I can tell, I am neither dead, nor completely recovered. But what of your own health?’’ I asked. I already knew from Henry that, aside from her growing deafness, she suffered from bouts of depression which she dealt with by rattling round here there and everywhere.

‘‘Baldwin,’’ she replied, ‘‘has tried me on a pair of artificial eardrums, but unfortunately they became infected. The pain made me think I should be mad, or dead, before morning. Thus, domage,’’ she added: ‘‘the trumpet.’’

‘‘I’m sorry,’’ I said.

‘‘Are you?’’ she asked sharply, but before I could reply she said, ‘‘Oh, of course you are, you know all about pain. I was forgetting. Insincerity is so common, and so trying. Forgive me, Alice.’’

She really is well-intentioned, I thought, but inclined to over-earnestness – and open-heartedness. It was unsettling. Her tiny foot tapped beneath her skirts. Tea was served. Wardy poked the fire while we munched on scones and sipped our tea.

‘‘Have you heard about ‘poor’ Gladys Evelyn?’’ she inquired.

‘‘Naturally,’’ I replied. Who hadn’t heard about the actress seduced by W. H. Hurlburt under the name ‘Wilfrid Murray’?

‘‘Marriage of course had been promised,’’ she pursued, ‘‘but the slippery H-M pleaded that the promise, if any, had been conditional upon Evelyn being ‘a chaste and modest woman’. Which – according to him – she ‘obviously was not’.’’

‘‘The verdict,’’ I added, ‘‘was announced in his favor – a hypocritical ‘no promise of marriage’.’’

The Sister

The Sister