- Home

- Lynne Alexander

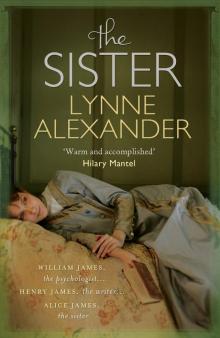

The Sister Page 11

The Sister Read online

Page 11

I shook my head. It could hardly be said that I had adjusted to anything or anywhere, new or old; or indeed to be living at all. I had simply woken up in England, having been picked up by Katharine and deposited over here. Which freed me of any responsibility. Piffle – of course I was responsible. I had agreed. I had allowed myself to be taken.

‘‘Can you speak, Alice?’’ He would not panic: ‘‘Tell me what you think is wrong.’’

How should I know? There were so many symptoms it exhausted me to think of them. I hissed into his ear, ‘‘I’m thinking of having a small pamphlet printed describing them.’’ He grinned broadly. Beneath the ink and soap, a pungent nervous sweat.

And the blood. How could I speak about that? I could not. The night before it had been so copious I’d imagined it soaking through the bedclothes and mattress onto the floor and from there – it would not stop – filling the rooms below and beyond. I’d thought of a tale, in the manner of Mr Poe, in which an invalid’s blood gathers force until the city’s streets are awash with it. The rats are thrilled, as are the wolves and, of course, the bats. Eventually the city and all its inhabitants drown in her blood. I’d considered describing it to Henry, asking him to write it down for me; but wisely had thought better of it.

He bent to retrieve the vial of pills that had fallen to the floor during the night.

‘‘Cannabis sativa,’’ I explained, ‘‘as prescribed by Garrod.’’

‘‘And it has helped?’’

‘‘As you see.’’ I could now speak, felt quite bright-eyed. I touched my stomach: ‘‘I could eat a horse.’’

‘‘I recommend something lighter on the digestion,’’ said Henry, ‘‘a fillet of sole perhaps.’’

I insisted on horse.

He pursed his lips. ‘‘So how was it with the good doctor?’’ he inquired. ‘‘Did his palpitating and stethoscoping meet with your approval?’’

I winced. ‘‘The man is an eel. I’m fed up with ‘great men of science’.’’

‘‘But, Alice,’’ Henry objected, ‘‘the last time you spoke of him you called him an avuncular Dutch cheese.’’

‘‘Invalid’s privilege.’’

‘‘So the honeymoon is over?’’

‘‘Unravelled like a marriage.’’

He sucked in his cheeks.

I recalled Garrod’s first visit. How he’d listened for a time with his open potato-face but after awhile held up his hand as if to say, enough of so many complaints at once. Having too many complaints, however, was the problem. He’d ordered nurse to sponge my spine with salt water – which had felt nice but had had no lasting beneficial effects. During his next visit he’d prescribed the hemp.

‘‘Is that all?’’ I challenged.

He spread his sausage fingers on his thighs. ‘‘I can find nothing organically wrong. The disturbances in your legs and stomach are entirely functional. But you needn’t worry,’’ he added, ‘‘the weakness will not lead to true paralysis.’’

‘‘But is it not unusual,’’ I pursued, ‘‘for a person to be so ill yet have no organic trouble?’’

‘‘Yes, very unusual indeed.’’

‘‘Well then, I should have thought you would like to do something for me.’’

But the great impotent could do nothing. As I now told Henry: ‘‘He slipped through my cramped and clinging grasp leaving me with no suggestion of any sort as to climate, baths or diet. The truth is he is entirely puzzled about me but does not have the manliness to say so.’’

Henry looked away, stricken, as if my harsh assessment must perforce include him. He, like everyone else, could only guess at this or that possibility. Gout had also been mentioned as an added complication, and ‘an excessive nervous sensibility’. But what I craved was a clear diagnosis, which neither he nor any medical man could give me. I pummeled the mattress with my fist:

‘‘What is wrong with me, Henry, what …?’’

He could not say. He tried distracting me with snippets of gossip and flirtation but I’d already begun drifting off. At some point I opened my eyes a crack and found Henry in the act of sketching me. He held his pencil stiffly – he was no artist after all – making awkward feathery strokes. Was he trying to convey the lingering pain etched in my sleeping features? Presently I shut my eyes again. What matter excellence? I felt his concentration trained on me; sensed him tracing the contours of my face as if stroking them with a finger: cheeks, nose, lips: my sister, my Alice. I basked in the glow; was comforted by a medicine no medical man had yet thought to prescribe.

I awoke much revived. Nurse propped me up with a bank of flaccid English pillows and fed me some milky tea. The attack was over: spiders, snakes, toucans all flown.

‘‘Better?’’ Henry guessed. At some point he’d moved to the captain’s chair.

I nodded. ‘‘Am I flushed, Henry?’’

‘‘Like a glow-worm on a dark night.’’

‘‘I believe I have come back,’’ I said.

He rose.

‘‘Before you go’’ – I wasn’t ready to lose him yet – ‘‘I suspect you have been drawing me while I snoozed on like some dullard at the theater?’’ I wondered if he would use me in one of his stories, the portrait of a pathetic snoring invalid.

He’d hid the drawing pad.

‘‘Don’t be alarmed, Henry, I won’t ask to see it; in fact, if you show it to me or anyone I’ll wring your neck.’’

He bowed theatrically.

‘‘And what did you observe as you drew?’’

‘‘Oh, a certain fluttering of the eyelids and …’’

‘‘And did I disgrace myself by snorting like a mad bull?’’

‘‘Aside from a few ladylike snufflings and a sudden cry of, ‘Down with the Queen’ – nothing remarkable.’’

Sixteen

Katharine. I pouted at her like a resentful infant before giving up in a whoosh of relief; let her have been carousing with warlocks on the moon for all I cared. As it happened, she had taken Louisa to Austria where she’d spent most of the time at a famous spa while Katharine immured herself among the archives. ‘‘Surely you didn’t spend your entire time in Vienna shut up with great historical tomes?’’ She would admit only to having seen a very domestic Don Giovanni featuring a half-dressed Donna Elvira. ‘‘Some were shocked of course.’’ ‘‘Not you?’’ ‘‘Not me. But you, Alice …?’’ She turned her attention on me, and I thought the wondrous thing was not why she’d left me in the first place but why she’d bothered to return at all.

‘‘Thanks to Henry’s ministrations,’’ I informed her, ‘‘I got through the worst of my ‘cataclysmic collapse’. Thanks to Henry,’’ I repeated, ‘‘I am now on the mend, as the English would have it, like an old sock.’’

‘‘Well praise be to Henry,’’ said she.

It was early spring and my first ‘outing’. We were headed for a stroll in The Green Park, that modest sylvan hideaway which Henry had once called a ‘pendant’ to the greater Park across the way – Hyde’s poor sister, as it were – with its ‘vulgar little railing’. But we preferred it. ‘‘It is a park of intimacy,’’ declared Katharine. ‘‘And democracy,’’ added I, observing some neighborhood children rampaging over the grass, as well as a number of oddbods asleep with newspapers over their faces. Henry had called it the salon of the slums, further infuriating Katharine: ‘‘I never know,’’ she’d declared, ‘‘when your brother is striking a pose, or just trying to annoy me.’’

We were crossing Piccadilly, about to leave the ‘huge, mild city’, as Henry had called it, behind us. ‘‘Not that it’s all that huge,’’ Katharine now said, looking up, as if to calculate the size of London by the circle of visible sky overhead while comparing it to New York or even Boston. ‘‘And rarely,’’ she added, ‘‘in my experience is it all that mild.’’

‘‘Henry,’’ I pointed out, ‘‘was no doubt referring to things more subtle than the weather.’’ My brother had writt

en of London’s fogs, its smoke and dirt and darkness, its wetness and distances, its ugliness, its heavy, dreary, stupid, dull, inhuman vulgarity, not to mention the brutal size of the place – such things were hardly to be admired – yet, in spite of all that, he found it a ‘mild’ place to live.

‘‘Henry,’’ I continued, ‘‘has described it as ‘an absence of intensity, a failure to insist’.’’ I went on, determined to clarify my brother’s meaning. ‘‘I guess he meant it takes a lot to grab this City’s attention.’’ ‘‘Alice’’ – she’d let go my arm and stood blocking out the light – ‘‘I am not interested in what Henry calls it, do you understand?’’

I understood. Perfectly.

‘‘I mean to say,’’ she corrected, her voice softening: ‘‘I’m more interested in your view of things.’’

Yet how, over the wind and the traffic noise, to express in what way the City’s mildness might ‘work’ for me, how it might allow me to be what I was in a way that America had not? As Henry knew, in Europe, whether idle or simply ill, I was somehow less of a burden than in America. I began picturing those pale, fine-featured, self-contained Americans – my friends who were now married and full of that determined American spirit, that get-up-and-go in spite of adversity – and I cringed at the thought of them; for it was they, paradoxically, the anaemic and the fagged, or so it seemed, who had left me feeling squashed and daunted. Whereas the robust ruddy-faced Englishwomen I’d met didn’t faze me in the least. But what if it was too easy? I began to wonder if London with its endless indulgence for weakness and prevarication would ever allow me to escape my destiny.

In the end all I could manage was a feeble: ‘‘But Kath my view is his view – at least in this. The only thing that gets people’s attention in this place is another turn of the Irish screw, or a divorce case that goes on for more than two days or …’’

She marched me on impatiently.

The day was windy, the sky a woolly glower above the blossoming cherries, and shifting, always shifting. We went through the gate and into a green and pink world.

‘‘Pink snow,’’ she calls it, leading me diagonally across. The fallen blossoms move in swirls, many of them landing in drifts around the enclosure walls, blown by the wind. Katharine guides my elbow lest I trip or lose my balance over a tree root or slip on a cherry petal. ‘‘I am not an ancient,’’ I mutter. At the other end, we negotiate the waves of horse-traffic round the ‘carousel’, with Queen Victoria watching over us, and make our way into St James’s Park. Before us, the lake.

‘‘It would not do for you to fall in,’’ Katharine comments wryly.

‘‘Nor for you to have to jump in and fish me out,’’ I rejoin.

But a top hat is rolling our way. Katharine drops my elbow leaving it to dangle in mid-air as she goes sprinting off after it. I watch thinking her heroic – the word is not too strong for one with her quick response, her elasticity and grace of gesture as she scoops up the hat then jogs off to return it to its owner, who bows melodramatically sweeping the retrieved hat before him. But when she returns, cherry-cheeked and breathless, I hear myself say in the surliest, yowlingest, complainingest, most spine-grating nasal-whine: ‘‘Am I to be left like that, for a hat?’’ To which she replies lightly, ‘‘Oh, I prefer a hat to you any day, especially a man’s bowler into which my entire head would fit.’’ A smile threatens the corners of my mouth even as I despair of myself. To be envious of a hat indeed!

After lunch we settled down with our books, one each side of the fire. I’d begun reading a new story of Henry’s in The Temple Bar Magazine called ‘Lady Barberina’, while Katharine pored over a compendium of dry educational statistics. What was the point, I asked, of all those numbers? She tried to convince me of their importance in revealing the educational disadvantage of females. Surely, I argued, one had no need of figures if one had eyes in one’s head to conclude that it was so. True, she agreed, but such figures were not intended for ‘people like us’ but for those in positions of influence who needed ‘proof’.

She paused, then said: ‘‘Mozart’s sister.’’

I laughed: what had that personage – had she existed – to do with educational statistics?

‘‘Oh, she existed alright: ‘‘the forgotten Nannerl. ‘‘She was clearly a prodigious musical talent, but there was her brother of course beside whom she could only fade into insignificance. Added to that, she was obliged to look after a cantakerous father; then she married a bullying widower with eleven children and moved to some god-forsaken rural exile. The only thing that kept her going were the letters from her brother. Then those stopped … she ended up blind.’’ Katharine dropped her own spectacles, shook her head, tried to laugh: ‘‘It was too awful translating such a tragic life.’’

‘‘So you went back to your statistics.’’

She looked away, as if I’d accused her of something unnatural.

We returned to our reading, but she was restless and kept looking over her shoulder out the window; while I was becoming increasingly disturbed by Lady Barbarina and her fate. ‘‘What is it?’’ asked Katharine, sensing my unease. I explained the situation in the story so far: Lady Barb, a wealthy, content Londoner, has been ‘claimed’ by the sour American – wittily named Jackson Lemon – and taken back to America.

‘‘I guess I’m anxious on her behalf.’’

‘‘Well you might be: any fool could predict she’s destined to be unhappy.’’

She was right of course, but the slur against Henry rankled. It was its very predictability, I argued, that made it so chilling. Lady Barb’s fate was sealed; nothing could stop it. At which I began to feel afraid: for myself and Katharine. Now that I was ‘well’, I realized, she expected me to go on recovering, growing stronger and stronger like a creature with no past or history of illness; almost as if I had never been the jangling, fluttering, palpitating, paralyzed bundle of knots and crosses that I so recently had been. True, I was greatly improved; but like a book, over-printed, with the harsh black text of my illness visible through the spidery, uncertain story of my so-called recovery. No, this ‘wellness’ of mine could only be a temporary if pleasant interlude; it would not, could not, last.

The room was quiet except for the flickering notes of the fire. ‘‘You must not depend on me,’’ I blurted out: ‘‘I mean, on my being well: I am unreliable.’’

‘‘Alice,’’ she said; and again – her voice a notch lower, almost failing: ‘‘Alice.’’ ‘‘Why must you look ahead at all? Why poke and prod until you end up …?’’

‘‘End up …?’’ I shot back.

‘‘Oh, why not just allow yourself to be well now?’’ And with that she rose, she would go out again; on her own, without me pulling at her, she would stride through parks and boulevards covering vaster distances than Henry. She would tire herself out, and then she would eat hugely and sleep. What must it be like, I wondered, to be so ferociously well?

*

‘‘Your brother, Miss,’’ announced the landlady.

‘‘You are writing,’’ Henry observed: ‘‘I must not interrupt.’’ He began reversing. ‘‘No, no, ‘‘ I felt myself color, ‘‘stay, please … I have finished, it is only … a letter to Aunt Kate.’’

The truth? I’d been scribbling some nonsense about a woman who buys herself a new wine-red dress with deep ruffles. She lives unrestrainedly going to operas and theatre openings and museums (her favorite is the Victoria & Albert); she even holds a salon twice a week. Then, one day, after receiving a few too many compliments on how well she looks, she begins to feel anxious. She senses her past lurking behind her, and imagines that while she is frittering away her time ‘being well’ it will be scuttling ahead of her like the wolf in the fairy story who knows the shortcut to Grandmamma’s house – and will inevitably one day be waiting for her, fangs out, ready to pounce.

‘‘Do sit, Henry.’’

He did so. ‘‘I have just met Katharine,’’ he waved, ‘‘a

t the end of the road.’’

I pictured him tipping his hat, shifting imperceptibly so that not so much as a scrap of fabric – Katharine having bunched up her skirts – could chum with his trouser leg. ‘‘And did she tell you about our walk in the Park and how she rescued a hat?’’ He waited. I described the scene, sparing nothing: the pink ‘snow’, the wind-roll of the hat, Katharine’s magnificent sprint, the motion of her arm reaching forth to sweep up the errant hat only seconds before its inevitable dive into the Lake, the fulsome bow of the gentleman. Henry, evidently immune to Katharine’s heroism, complimented me on ‘the exquisite detail’ of my narration.

‘‘Katharine is not a detail,’’ I snapped, ‘‘she is my dear friend … my companion.’’

He stood corrected. We sipped our tea. He told me about his own long perambulation around the suburbs of London and how, having returned ‘weak with inanition’, had taken a table at some godforsaken railway hotel …

‘‘You were hungry, I take it?’’

He simpered. He’d been presented with nothing more than a plate containing a trio of cold mutton, a pot of mustard and a chunk of bread.

A feast to me, it sounded. ‘‘Whatever was the problem, Henry?’’

‘‘Potatoes,’’ he lamented, imitating the water: We do not serve potatoes, sir, after nine p.m.

‘‘Poor Henry,’’ said I scratchily.

‘‘However,’’ he proclaimed, ‘‘I have survived the denial, as you see.’’

He looked a long way from starvation, it was true. After a pause I mentioned his cruel little story.

‘‘Which one?’’ asked my witty brother.

‘‘Lady Barbarina.’’

‘‘Ah, and you find it cruel that …?’’

‘‘That Lady Barb should have to be removed from her own environment into a strange one where she is doomed to unhappiness. To make it worse, there is the comparison with her sister, Lady Agatha, who is horribly happy in America.’’

The Sister

The Sister